For her descendants

Wayland and Peter; Easter, Emily, Mopsa, Thoby and Zoe;

Nicola, Falcon and Dafila; Alice and Remel, Louis and Theo; Arthur; Joe, Lily

and Tom; Maud, Archie and Tolly; Emily, Dan, Lucy-Kate and Ben;

Freddie and Helena; Lucy; Peter and Amber;

and my Isabel.

And unto the next generation...

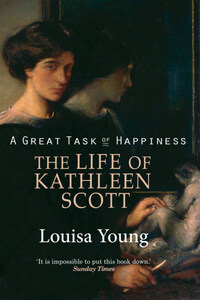

In the course of my parents’ fortieth wedding anniversary party in 1988, I was sitting on the old green velvet sofa at their house in Bayswater with my ancient cousin Verily, who was hooting with laughter. She told me that a good sixty years ago she’d been sitting on that same sofa in that same room with my grandmother Kathleen, her aunt, and that I was saying exactly the same thing that Kathleen had been saying. I think it was something about how lovely it is to sleep out of doors. Kathleen always slept out of doors, given half the chance. In Bayswater she slept on the balcony.

Kathleen was my father’s mother. She was born in 1878 and died in 1947 so I never knew her, but statues she had made were all over the house and garden, and sometimes my father would point one out in a public place: Adam Lindsay Gordon in Westminster Abbey; Lloyd George in the Imperial War Museum, and The Man Who Wasn’t My Grandfather on Waterloo Place. I knew he wasn’t my grandfather because my grandfather had only one arm and wasn’t all bundled up. Gradually I realised who he was: Con, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, her first husband; and that he was heroic and tragic and had died of cold and hunger in a tent in a blizzard in the Antarctic, having got to the South Pole too late. I knew this was unspeakably sad but I was worried too because if he (and Oates and Evans and Bowers and Wilson) had come back, Kathleen would never have married my grandfather, and my father and I and my five siblings would never have been born. I wondered if Uncle Pete, who was nine months old when he last saw his father, minded about us. I realised quite soon that he probably didn’t, as he had named a family of swans after us.

Kathleen had written a short autobiography, largely for her own pleasure, in 1932; it was published along with a tiny selection from her thirty-six years’ worth of diaries after her death. I read it when I was sixteen, and was delighted to find that a grandmother could have lived like a vagabond on a Greek island, could have had friends who got pregnant out of wedlock, could have been annoyed by the hounding of the press, could have worried about what to wear, could have fallen in love and ridden with cowboys, could have run away to Paris to be an artist, and to Macedonia to tend to refugees, could have been financially independent and brought up a son alone. Equally I was shocked to find that a grandmother—my grandmother—could have not supported female suffrage, could have visited South Africa and not exploded at the injustices there, could have moved happily in circles where people referred to ‘little Jews’. I had to accept that I could not in justice expect one woman within her generation to be in every way ahead of that generation in matters of humanity and justice. Things unacceptable to me now were generally accepted then; some of them (not all) Kathleen accepted.

But then the humanity in her friendships, with passing strangers or with famous people—George Bernard Shaw, Isadora Duncan, Asquith, Sir James Barrie, Lawrence of Arabia, Max Beerbohm, Austen Chamberlain, Rodin, Colonel House—delighted me. The details of how a woman was, and how women could be, in those days, were fascinating. She was funny and adventurous and innocent and proud. She travelled all over the world. I was pleased to be descended from her.

I was thirty before I realised I could read all her diaries, written almost every day for thirty-six years. She started them for Con when he went south; they were to be a record for him of their son and of her day-to-day activities. After she learnt that Con was not coming back she kept them up. No one knew she did. Her handwriting races along (illegible unless you really practice reading it) recording adventures, anecdotes and observations, interspersed with photographs and little sketches, from 1910 to 1946. They cover politics and exploration, art and sex, literature and travel, Mexican trains and plastic surgery, love and death, folly and creativity, childbirth and flying, iguanas and vicars and eating chicken sandwiches out of her coronet at the coronation of George VI. They notably lack self-absorption, self-pity and self-indulgence. I realised that the story sitting in her papers—she kept many letters too—at the University Library in Cambridge was begging to be searched out.