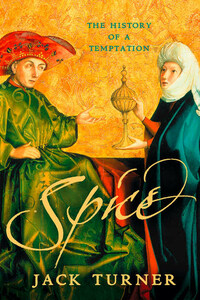

A certain Christopher Columbus, a Genoese, proposed to the Catholic King and Queen, Ferdinand and Isabella, to discover the islands which touch the Indies, by sailing from the western extremity of this country. He asked for ships and whatever was necessary to navigation, promising not only to propagate the Christian religion, but also certainly to bring back pearls, spices and gold beyond anything ever imagined.

Peter Martyr, De Orbe Novo, 1530

One day at Aldgate Primary School, after the dinosaurs and the pyramids, we did the Age of Discovery. Our teacher produced a large, illustrated map, showing the great arcs traced across the globe by Columbus and his fellow pioneers, sailing tubby galleons through seas where narwhals cavorted, whales spouted and jowly cherub heads puffed cotton-wool clouds. Parrots flew overhead while jaunty, armour-clad gents negotiated on the beaches of the new-found lands, asking the natives if they would like to convert to Christianity and whether by chance they had any spice.

Neither request struck us ten-year-olds as terribly reasonable: we were a pagan, pizza-eating lot. As for the spices, our teacher explained that medieval Europeans were afflicted with truly appalling food, necessitating huge quantities of pepper, ginger and cinnamon to disguise the tastes of salt and old and rotting meat â which, being medieval, they then shovelled in. And who were we to disagree? It made a lot of sense, particularly relative to the generally perplexing matter of schoolboy history, whether it was frostbitten Norwegians dragging their sleds to the South Pole, explorers dying of thirst in the quest for non-existent seas and rivers, or knights taking the cross to capture the Holy Sepulchre from the infidel â all, from a schoolboyâs perspective, strangely perverse and pointless pursuits. The discoverers were somehow more intelligible, more human: our food at school was lousy, but theirs was so dismal that they sailed right around the world for relief. And to an Australian ten-year-old this was not only plausible but highly relevant: so this was why we were colonised by the English.

There was some truth in my potted ten-year-old perspective, albeit radically streamlined. The first Englishmen in Asia were indeed looking for spices, as were the Iberian discoverers before them (whereas Australia, not having any spice, was left till later). Spice was a catalyst of discovery and, by extension â in that much-abused phrase of the popular historian â the reshaping of the world. The Asian empires of Portugal, England and the Netherlands might be said with only a little exaggeration to have sprouted from a quest for cinnamon, cloves, pepper, nutmeg and mace, and something similar was true of the Americas. It is true that the hunger for spices galvanised an extraordinary, unparalleled outpouring of energies, both at the birth of the modern world and for centuries, even millennia, before. For the sake of spices, fortunes were made and lost, empires built and destroyed, and even a new world discovered. For thousands of years this was an appetite that spanned the planet and, in doing so, transformed it.

And yet to modern eyes it might seem a mystery that spices should ever have exerted such a powerful attraction, however bad the food: mildly exotic condiments, we might think, but hardly worth the fuss. In an age that pours its commercial energies into such unpoetical ends as arms, oil, ore, tourism and drugs, that such energies were devoted to the quest for anything quite so quaintly insignificant as spice must strike us as mystifying indeed.