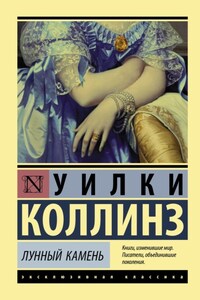

In the year 1928, when the boom in âseriousâ detective-novel writing which began round about the first world war was nearing its height, and the âart and scienceâ of it was being very seriously discussed, an eminent detective novelist, in a forty-five page introduction to a vast collection of stories, let fall the opinion that âThe Moonstone is probably the finest detective story ever written.â Until that date, Wilkie Collins had been slightly regarded by connoisseurs, unless they were specialists in lesser Victorian fictionââIn the British Museum catalogue,â discovered the shocked author of this encomium, âonly two studies of this celebrated mystery-monger are listed: one is by an American, and the other by a German.â Thereafter, however, he became great; he was almost canonised as the direct ancestor of Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Thorndyke, Hercule Poirot, Lemmy Caution, and all the tribe.

It is interesting, therefore, to observe that Collins himself did not think of The Moonstone as a detective story at all. This was not because the genre had not yet come into existence. The solution of a crime by the exercise of pure ratiocination on the part of a single mind had been set out in classic form twenty years before by Edgar Allan Poe in The Murders in the Rue Morgueâin which, incidentally, the character-scheme of Dupin plus adoring chronicler set the convenient pattern which was repeated in Holmes plus Watson, Poirot plus Hastings, and many other subsequent combinations. In France, also, the roman policier was developing fast in the hands of Gaboriau and Du Boisgobey. Collins, if he had wanted to write, âthe finest detective story,â had no lack of models; but he did not. What he himself thought of the intention of his own novelâand he presumably knew what he meant to doâhe set out in the preface:

âThe attempt made, here, is to trace the influence of character on circumstances. The conduct pursued, under a sudden emergency, by a young girl (Rachel Verinder) supplies the foundation on which I have built this book.â

He goes on to say that he has endeavoured to make his subsidiary characters behave as they would have behaved; and adds that his account of the âphysiological experimentââthe dosing of Franklin Blake with laudanum in order to induce him to repeat his sleep-walking actions on the night of the disappearance of the Moonstoneâis based on a careful study of books and of living authorities. Clearly what interested the author of The Moonstone was not the detail of the theft of the gem and the subsequent tracking down of those responsible, but the effect of the whole series of events on the behaviour of his characters. That is to say, he was writing a novel with a plot, not a cross-word puzzle.

There are, of course, elements in The Moonstone which have since become classic detective-story-componentsâso classic, indeed, that later writers seeking to avoid monotony have drawn especial attention to the fact that they are not using the established formula. There is the very stupid policeman, in this case Superintendent Seegrave, who is a worthy ancestor of Lestrade, Inspector Japp, and of all the police officers whom Dr. Thorndyke bewildered in his day. There is the crime brought home, after suspicion has been well distributed to the most unlikely persons; although, on the other hand, Collins is scrupulously fair and makes no attempt to confuse the reader by presenting the real criminal as a person too attractive to be mistrusted. There are some clues, notably the paint-stained nightgown, though the paint-stained nightgown does not solve the mystery; it is, in fact, not much more use to Sergeant Cuff than a blood-stained nightgown was to that unfortunate Detective Whicher whom some suppose to have been the real life model for the Sergeant. (The Constance Kent case, as a matter of fact, except for the incident of the nightgown, bears practically no resemblance to the plot of The Moonstone.) Finally, there is the clear attempt to build up Sergeant Cuff into a âcharacter,â by stressing his peculiar physical appearance and his reiterated interest in the growing of roses. This might legitimately be regarded as a foreshadowing of the long array of detectives noted for personal idiosyncrasiesâSherlock Holmes above all, but including also Lord Peter Wimsey, with his collectorâs mania, the blind Max Carrados of Ernest Bramah, Baroness Orczyâs Old Man in the Corner, who fiddled with string, and a dozen others, as well as some whose distinguishing characteristic is proudly stated to be that of possessing none whatever.