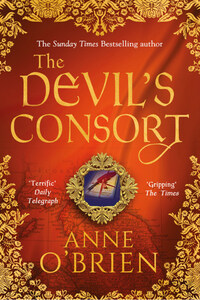

Devil’s Consort

ANNE O’BRIEN

![]()

All the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination of the author, and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing the same name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the author, and all the incidents are pure invention.

All Rights Reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Enterprises II B.V./S.à.r.l. The text of this publication or any part thereof may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, storage in an information retrieval system, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the prior consent of the publisher in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

HQ is an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Published in Great Britain 2011.

HQ 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

© Anne O’Brien 2011

ISBN 978-1-4089-3583-5

Version: 2018-07-18

ANNE O’BRIEN taught History in the East Riding of Yorkshire before deciding to fulfil an ambition to write historical fiction. She now lives in an eighteenth century timbered cottage with her husband in the Welsh Marches, a wild, beautiful place renowned for its black and white timbered houses, ruined castles and priories and magnificent churches. Steeped in history, famous people and bloody deeds, as well as ghosts and folklore, the Marches provide inspiration for her interest in medieval England.

Visit her at www.anneobrienbooks.com

For George, as ever, with love.

And for my father, who gave me my first

love of history.

If all the world were mine From the seashore to the Rhine,

That price were not too high

To have England’s Queen lie

Close in my arms.

—Anonymous German troubadour

An incomparable woman … whose ability was the admiration of her age.

Many know what I wish none of us had known.

This same Queen in the time of her first husband went to Jerusalem.

Let no one say any more about it …

Be silent!

—Richard of Devizes

All my thanks to my agent, Jane Judd,

who continues to be enthusiastic about my versions of medieval history.

And to Helen and all her experts at Orphans Press,

who make my hand-drawn maps and genealogy look splendidly professional.

July, 1137:

The Ombrière Palace, Bordeaux.

‘WELL, he’s come. Or at least his entourage has—I can’t see the royal banners. Aren’t you excited? What do you hope for?’

Aelith, my sister, younger than I by two years and still with the enthusiasms of a child beneath her newly developing curves, battered at me with comment and questions.

‘What I hope for is irrelevant.’ I studied the busy scene.

I had got Louis Capet whether I liked it or not.

I had thought about nothing else since my father’s deathbed decision to place me under the hand of Fat Louis—the King of France, no less—had settled my future beyond dispute. I wasn’t sure what I thought about it. Anxiety at the choice vied with a strange excitement. Queen of France? It had a weighty feel to it. I was not averse to it, although Aquitaine was far more influential than that upstart northern kingdom. I would be Duchess of Aquitaine and Queen of France. I need not inform my newly espoused husband which of the two I considered to be the more important. Although why not? Perhaps I would. I would not be disregarded in this marriage.

I was Eleanor, daughter and heir to William, the tenth Duke of Aquitaine, the eldest of my father’s children, although not born to rule. Not that I, a woman, was barred by law from the honour, unlike in the barbaric kingdom of the Franks to the north, but once I had had a younger brother who had been destined to wear the ducal coronet. He, William—every first-born son was called William—was carried off by a nameless fever, the same as relieved my mother Aenor of her timorous hold on life. Leaving me. In the seven years since then I had grown used to the idea. It was my right to rule.

But I was nervous. I did not think I had ever been nervous before: I had had no need, as my father’s heir. My lands were vast, wealthy, well governed. I had been brought up to know luxury, sophistication, the delights of music and art. I was powerful and—so they said—beautiful. As if reading my mind, my troubadour Bernart began to sing a popular verse.