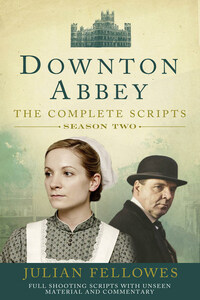

HarperCollinsPublishers

77â85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

FIRST EDITION

Text © Julian Fellowes 2014

Cover photographs © Nick Wall 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

A Carnival Films/Masterpiece Co-production

Downton Abbey Series 1â4 and all scripts © 2009 to 2014 Carnival Film & Television Limited. Downton Abbey logo © 2010 Carnival Film & Television Limited. Downton Abbey and the Downton Abbey device are trademarks of Carnival Film & Television Limited. Carnival logo © 2005 Carnival Film & Television Limited.

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Julian Fellowes asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007481545

Ebook Edition © November 2014 ISBN: 9780007481125

Version: 2014-11-05

At the end of the second series, we left our characters facing the new decade and the new postwar world. Matthew may have (finally) proposed, but little else was settled about the future of the Crawley family. As a matter of fact, I have always been interested in the 1920s, and now we were finally there. It strikes me as a curious, almost nebulous, time, an impression that was strengthened by the accounts of my great-aunts, whom I knew well as a young man and who had vivid memories of the era. My eldest great-aunt, Isie, had been born in 1880 and so this was the decade of her forties. Her husband had died of wounds in the last days of the war and, with an infant son, she had essentially to negotiate those years alone. According to her, at the very beginning nobody was quite sure what had really changed, and what would go back to the way it had been before the war. As time went on, it became increasingly clear that fundamental change had occurred and nothing would ever be the same again, but it took a little while for this to sink in, and it was that very uncertainty that attracted me to the period as a background to a family drama.

There were milestones, markers, along the way. When Lloyd George suddenly ended agricultural relief, without warning, in 1922, he struck a blow against the landowners, many of whom had been in debt since the agricultural depression of the last decades of the nineteenth century, and had taken out loans and mortgages, thinking and hoping, Micawber-like, that something would turn up. But of course for the majority nothing turned up. There was also an anomaly, which I am sure was deliberate, that selling land was still regarded as a capital gain, on which, in those days, there was no tax. So your option was either to lumber on with an erratic farming income, subject to heavy income tax, or to cash in your chips for a tax-free lump sum. Inevitably, and I believe as Lloyd George intended, something like a third of England was sold between the wars.

Counterbalancing that, and creating the baffling illusion of continuity, the new rich â and there were many â continued to spend their fortunes in the old way. I donât mean these were war profiteers in a pejorative sense, but wars do certainly make fortunes and, besides them, there were industrialists and manufacturers and, perhaps most prominently in this company, the powerful newspaper magnates, all of whom aped the Victorian model and purchased great houses and great estates on which to lavish their newly gotten gains. So, there was this slightly bewildering contradiction of old families going under all over the place, but huge palaces, in the ownership of Lord Rothermere or Lord Beaverbrook and their kind, being run with an extravagance scarcely seen since the 1890s.

Being rich in a new way was something being developed by the Americans, and it would not really reach these shores until after the Second World War. The Americans never felt the European imperative to separate themselves from the source of their money, and would cheerfully go into the bank or the office every morning, long after they had taken the reins of New York Society. They had their palaces, too, of course, at Newport or on Long Island, but they felt no need to imitate farmers with profitless estates. Their model is much more recognisable to the present generation when, now, riches are more likely to be devoted to helicopters, Manhattan apartments and houses in the South of France than to the purchase of 20,000 acres of the North Riding. But in the 1920s you had this strange contrast: the new rich creating the illusion that the old way of life would continue, while many of the old rich were chucking in the towel.