Translator: Jorge Gonzalez Casanova (for Frida Kahlo’s Writings)

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

© Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo № 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

![]()

1. The Dream or The Bed, 1940. Oil on canvas, 74 × 98.5 cm. Collection Isidore Ducasse, France.

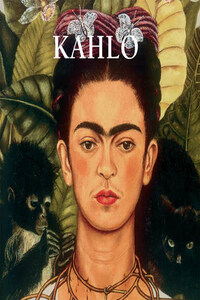

2. Self-Portrait, 1930. Oil on canvas, 65 × 55 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Her serene face encircled in a wreath of flaming hair, the broken, pinned, stitched, cleft and withered husk that once contained Frida Kahlo surrendered to the crematory’s flames. The blaze heating the iron slab that had become her final bed replaced dead flesh with the purity of powdered ash and put a period – full stop – to the Judas body that had contained her spirit. Her incandescent image in death was no less real than her portraits in life. As the ashes smoldered and cooled, a darkness descended over her name, her paintings and her brief flirtation with fame. She became a footnote, a “promising talent” forever languishing in the shadow of her husband, the famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, or as art critic stated with a yawn over one of her works: “…painted by one of Rivera’s ex-wives”.

Frida Kahlo should have died 30 years earlier in a horrendous bus accident, but her pierced, wrecked body held together long enough to create a legend and a collection of work that resurfaced 30 years after her death. Her paintings struck sparks in a new world prepared to recognise and embrace her gifts. Her paintings formed a visual diary, an outward manifestation of her inward dialog that was, all too often, a scream of pain. Her paintings gave shape to memories, to landscapes of the imagination, to scenes glimpsed and faces studied. Her paintings, with their symbolic palettes, kept madness (yellow) and the claustrophobic prison of plaster and steel corsets at arm’s length. Her personal vocabulary of iconic imagery reveals clues as to how she devoured life, loved, hated, and perceived beauty. Her paintings, seasoned with words and diary pages and recollections of her contemporaries, reward us with a life lived at a fractured gallop, ended – possibly – at her own will, and left behind a courageous collective self-portrait, a sum of all its parts.

The painter and the person are one and inseparable and yet she wore many masks. With intimates, Frida dominated any room with her witty, brash commentary, her singular identification with the peasants of Mexico and yet her distance from them, her taunting of the Europeans and their posturing beneath banners: Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Expressionists, Surrealists, Social Realists, etc. in search of money and rich patrons, or a seat in the academies. And yet, as her work matured, she desired recognition for herself and those paintings once given away as keepsakes. What had begun as a pastime quickly usurped her life. Frida’s conversations were peppered with street slang and vulgarisms that belied her petit stature, Catholic upbringing and conservative love of traditional Mexican customs. While strolling a New York street wearing her red-trimmed Tehuantepec dress, jewelry studded with thousand-year-old jade and with a scarlet reboso shawl across her shoulders, a small boy approached and asked, “Is the circus in town?” She was a one-person show in any company, a Dadaist collection of contradictions.

Her internal life caromed between exuberance and despair as she battled almost constant pain from injuries to her spine, back, right foot, right leg, fungal diseases, many abortions, viruses and the continuing experimental ministrations of her doctors. The singular consistent joy in her life was Diego Rivera, her husband, her frog prince, a fat Communist with bulging eyes, wild hair and a reputation as a lady killer. She endured his infidelities and countered with affairs of her own on three continents consorting with both strong men and desirable women. But in the end, Diego and Frida always came back to each other like two wounded animals, ripped apart with their art and politics and volcanic temperaments and held together with the tenuous red ribbon of their love.

Her paintings on metal, board and canvas with their flat muralist perspectives, hard edges and unrepentant sweeps of local colour reflected his influence. But where Diego painted what he saw on the surface, she eviscerated herself and became her subjects. As Frida’s facility with the medium and mature grasp of her expression sharpened in the 1940s, that Judas body betrayed her and took away her ability to realise all the images pouring from her exhausted psyche. Soon there was nothing left but narcotics and a quart of brandy a day.

Diego stood by her at the end as did a Mexico slow to realise the value of its treasure. Denied singular recognition by her native land until the last years of her life, Frida Kahlo’s only one-person show in Mexico opened where her life began and acted out its brief 47-year arc. When she was gone, the eyes of that life remained behind, observing us from the frame with a direct and challenging gaze.