Dipylon Head, Dipylon, Athens, c. 600 B. C. Marble, h: 44 cm. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

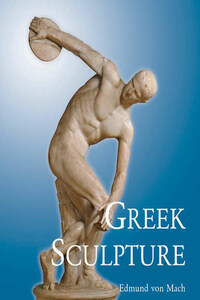

The study of Greek sculpture was unknown two hundred and fifty years ago. Winckelmann[1] was the first to study it, and to publish a book on the subject in 1755. The excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum, the removal of the Parthenon sculptures to London by Lord Elgin, and above all, the regeneration of Greece and the subsequent rich finds in her soil, added zest to the continually growing interest in this new study.

In the eighteenth century people were unable to properly judge ancient art because they possessed few originals and were obliged to look through the spectacles of a later Roman civilisation. Animated by a scientific spirit, people of the nineteenth century probed deeper. The spade of the excavator brought long-forgotten treasures to light; scholars trained in the severe school of philology arranged and classified the material, and little or nothing was left to the art critic. The subject, on the whole, was in the hands of the scientific archaeologists, who presented it in more or less exhaustive histories of Greek sculpture or Greek art. All their books follow the historic development. They are histories of ancient artists.

Such a treatment of the subject, although bringing order out of the preceding century’s chaos, made a clear understanding of the spirit of Greek sculpture impossible; for it overburdened the books with such facts as are interesting only to the specialist for use in further discoveries, and cannot legitimately appeal to the artistic public. The archaeological discussions, therefore, largely account for the present neglect of ancient art on the part of artists and intelligent laymen. The eighteenth-century writers generalised without sufficient facts at their disposal; the nineteenth-century scholars collected the facts, and it therefore becomes our duty today to present the lessons which can be learned from them and to introduce the reader to the spirit and the principles of Greek sculpture.

The spirit of Greek sculpture is synonymous with the spirit of sculpture. It is simple, and therefore defies definition. We may feel it, but we cannot express it. The reason it has lost its power today is that we have listened to what has been said about it instead of coming into contact with it. No amount of book knowledge makes up for the lack of familiarity with original pieces of sculpture. “Open your eyes, study the statues, look, think, and look again,” is the precept to all who would learn to know Greek sculpture. Some introductory assistance and guidance, to be sure, should be accepted; they clear one’s mind of prevailing misconceptions. Suggestions in this direction, however, often do more than exhaustive discussions, for they stimulate individual, thought.