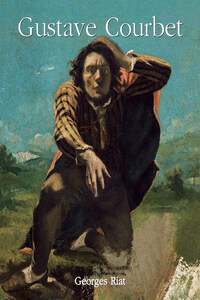

1. Self-Portrait, c. 1850–1853.

Oil on canvas, 71.5 × 59 cm.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

The artist Jean-Désiré-Gustave Courbet was born in Ornans on the 10th of June 1819. Most of Courbet’s biographers say that he was of farming stock, and was a farmer himself. The latter statement is wrong, while the former should be clarified. His father, Régis Courbet, was an important landowner. He owned an estate on a plateau, which although fragmented, as was often the case in Franche-Comté, spread over the communities of Flagey, Silley and Chantrans.

A letter from Max Buchon to Champfleury depicts Régis Courbet in a lively, picturesque way: “The father is much more idealistic, a constant talker and nature-lover, sober as an Arab, tall, long-legged, quite handsome in his youth, immensely affectionate, never knowing what time it is, never wearing out his clothes, a seeker of ideas and agricultural innovations, who invented his own special harrow, and who, in spite of the fact that he had a wife and daughters to support, farmed in a way that made him little profit.” The old folks in the area still recall that “improved” harrow, which destroyed the crops, as well as a certain carriage, with a fifth wheel on the back which held the food baskets for the hunt. These inventions and a few others in the same vein earned him the nickname, cudot, which in the local dialect described someone possessed by pipe-dreams. He was on the whole an excellent fellow who, had he been more practical, would have let out his lands to sharecroppers and lived the life of a country squire.

Courbet’s mother, Sylvie Oudot, was a relative of the jurist Oudot, a professor of law in Paris, and was quite different. A hard-working woman, constantly busy patching up the damage from her husband’s blunders and hare-brained schemes, she was the one who actually ran the farm, while still found the time to bring up her children and relax in the evenings by playing the flute.

Gustave was the firstborn. After him came three daughters, whom the artist quite often included within his paintings, most notably in Young Women from the Village. They were the somewhat sickly Zélie, who played the guitar; the overly sentimental Zoé, who had a fiery imagination; and Juliette, the youngest, lively and devout, and who at an early age fell in love with the piano. Added to this family circle were Grandfather and Grandmother Oudot, objects of Courbet’s constant affection, so the artist grew up in an atmosphere which was much more bourgeois than peasant, though not so bourgeois that the young man was deprived of the wonders of nature, and not so peasant that there was any question of his becoming anything but an educated professional.

At first glance, it is easy to see the imprint of both nature and nurture upon Courbet’s personality. His Grandfather Jean-Antoine Oudot, a raging revolutionary of 1793 and fervent follower of Voltaire, taught him by example to espouse republican, anticlerical ideas; his father’s outrageous behaviour explains some of his own, as well as his pride, vanity, and pursuit of glory; from his mother he received, in spite of appearances, a refinement and thoughtfulness, examples of which are plentiful throughout his life, but which he kept carefully hidden from all but those closest to him. His long ancestry of wine growers and farmers also made him a man of the soil, a terrien, with all that this word implies in terms of health, robustness, perseverance, determined possessiveness and occasionally a certain vulgarity, along with an uncompromising frankness and a roughness of character. In short, he inherited that rare flame of genius that made it possible for him to become one of the greatest artists who ever lived.

In 1831, his parents sent him to the lower seminary in Ornans, which prepared pupils not only for the upper seminary, but also for secular careers. Courbet did not do well there, being unable to take an interest in Latin, Greek or mathematics and frequently playing hooky. He was known for his skill in chasing butterflies and his knowledge of the surrounding trails, so much so that he was picked to be the guide on Sunday outings.

If Courbet paid little attention to classical studies, it was a different story when it came to drawing, and even painting, which soon began to interest him. From that moment on his art teacher, “Father Beau,” had no pupil who was more attentive or serious. It was not long before the pupil knew as much as his teacher. Mademoiselle Juliette Courbet religiously kept albums filled with his drawings; studies of flowers, profiles, heads, sketches of landscapes, fantasies, all of which bear witness to his fervour for drawing. Such a calling was not at all to the liking of Courbet’s father, who wanted his son to study at the École Polytechnique. Therefore in October 1837 he sent him to study philosophy at the royal secondary school in Besançon, thinking that boarding school would straighten him out. But in fact the opposite occurred, and the many letters from the son to his parents show how poorly he adjusted to this existence which was so new to him.