Self-Portrait of Hokusai at Eighty-Three, 1842.

Ink on paper, 26.9 × 16.9 cm.

Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde, Leiden.

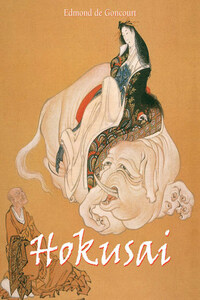

Hokusai’s talent travelled across land and sea to Europe long ago. But his work, so original, so diverse, and so prolific, still remains misunderstood. It is true that, even in the artist’s homeland, though he has always been immensely popular, his work has not been received with the same fervour by the academy and by the elite as by the Japanese people. Was he not reproached, in his own time, for only doing ‘vulgar paintings’? Then, however, few artists knew how to delve into the potential of drawing techniques and methods as he did. What artist can vaunt his ability to draw with his fingernails, his feet, or even his left hand (if right-handed) or inverted, with such virtuosity, that it seems to have been drawn in the most conventional way?

Hokusai illustrated more than 120 works, one of which, the Suiko-Gaden, consisted of ninety volumes. He collaborated on about thirty volumes: yellow books and popular books at first, eastern and western promenades, glimpses of famous places, practical manuals for decorators and artisans, a life of Sakyamuni, a conquest of Korea, tales, legends, novels, biographies of heroes and heroines and the thirty-six women poets and one hundred male poets, with songbooks and multiple albums of birds, plants, patrons of new fashion, books on education, morals, anecdotes, and fantastic and natural sketches.

Hokusai tried everything, and succeeded. He was tireless, multitalented, and brilliant. He accumulated drawings upon drawings, stamps upon stamps, informing himself very specifically about his compatriots, their work, and their interests, and about the people in the streets, those in the fields, and those on the sea. He opened the gates to the walls that hid brilliant courtesans, their silks and embroidery, and the large belt knots spread across their chests and stomachs. He frightened observers with apparitions from his most awful and stirring, fantastic imagination.

To understand the art of a very particular, distant people, it is not sufficient to learn, more or less well, their language; it is necessary to penetrate their soul, their tastes – one must be the obedient student of this soul and these tastes. It is, after all, founded on love, the profound ecstasy that artists feel in expressing their country. They love it passionately, they cherish its beauty, its clarity, and they try to reproduce its life from the heart. A happy affliction, Hokusai was an eminent representative of those who work incessantly.

Women with a Telescope, from the series The Seven Bad Habits (Fu-ryu-nakute nana kuse), late 1790s.

Nishiki-e (polychrome woodblock print), 36.8 × 24.8 cm.

Kobe City Museum, Kobe.