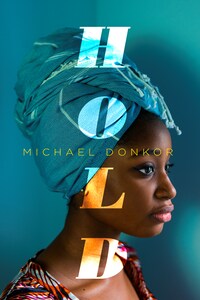

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © Michael Donkor 2018

Cover photograph © Plainpicture/R. Mohr

Cover design by Jack Smyth

Michael Donkor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

‘Michicko Dead’ from The Great Fires: Poems, 1982–1992 by Jack Gilbert, copyright © 1994 by Jack Gilbert. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008280345

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008280369

Version: 2018-06-07

For Patrick Netherton and Grace Opoku

Aane – Yes

Aba! – Exclamation of annoyance, disdain or disbelief

Aboa! – You beast!

Abrokyrie – Overseas

Abrokyriefoɔ – Foreigners

Abusuafoɔ – Extended family

Adɛn? – Why?

Adjei! – Exclamation of surprise or shock

Agoo? – May I come in?

Akwaaba – Welcome

Akwada bone! – Naughty child!

Amee – Please enter

Ampa – It’s true

Ewurade – God

Ɛfɛpaaa – Very nice

Fri hɔ! – Go away!

Gyae – Stop

Gye nyame – Traditional symbol meaning ‘only God’

Hwɛ – Look

Hwɛw’anim! – Look at your face!

Kwadwo besia – An ‘effeminate’ man

Maame – Miss/Mistress

Me ba – I am coming

Me boa? – I lie?

Me da ase – I thank you

Me nua – My sibling

Me pa wo kyew/me sroe – Please (I beg you)

Me yare – I am sick

Nananom – Elders

Oburoni – White person

Oburoni wawu – Second-hand clothes (‘the white man is dead’)

Paaa – Sign of emphasis

Sa? – Really?

Wa bo dam! – You are mad!

Wa te? – Do you hear?

Wa ye adeɛ – Well done

Wo se sɛn? – What did you say?

Wo wein? – Where are you?

Wo ye … – You are …

Won sere? – You won’t laugh?

Yere – Wife

The coffin was like a neat slice of wedding cake. Looping curls of silver and pink, fussy like best handwriting, wound around the box. It waited by the gashed earth that the men would rest it in. The mourners admired, clucking. Belinda made herself look at it. Her phone vibrated in her handbag but she let it rumble on. She brought her ankles together, fixed her head-tie and straightened her dress so that it was less bunched around her breasts. She passed her hand over her puffy face and then saw that eyeliner had rubbed onto her palm in streaks.

Belinda’s inspection of her messy hands was interrupted by the shouting of the young pallbearers on the opposite side of the grave. They stripped off and swirled the cloths that had been draped over their torsos moments before, then called for hammers. Three little boys, perhaps six or seven years old, flitted back with tools heavier than their tiny limbs. The children hurried off with handfuls of sweet chin chins, nearly falling into the hole not meant for them and only laughing light squeals at how narrowly they had avoided an accident. Belinda wondered if she had ever laughed like that when she was their age.

The men started to thud away the casket’s handles, eager for the shiniest decorations, the ones that would fetch the highest prices in the market. She knew it was what always happened at funerals, and that the bashing and breaking was no worse than anything else she had seen in the last few hours – but as the men’s blows against the handles kept on coming, the sound became a hard hiccupping against Belinda’s skull. Her chin jutted forward like it was being pulled and her whole body tightened. Belinda tapped the heel of her court shoe into the red earth, matching her galloping blood. Soon, wrenched free of its metal, the coffin’s surfaces were all marked with deep black gouges.

Someone tried to move Belinda with a shove. She remained where she stood. The pallbearers strutted and touched their muscles. Some yelped for the crowd to cheer. There were whines from older mourners about sharing, relatives and fairness.

‘Sister!’ an excitable man said, pushing a brassy knob towards Belinda. She let it fall from his grasp and roll at her feet. It was not enough.

Daban, Kumasi – March 2002

Belinda fidgeted in the dimness. She sat up, drawing her knees and the skimpy bedsheets close to her chest. Outside, the Imam’s rising warble summoned the town’s Muslims to prayer. The dawn began to take on peaches and golds and those colours spread through the blinds, across the whitewashed walls and over the child snuffling at Belinda’s side.