HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2015

© Duncan Barrett and Nuala Calvi 2015

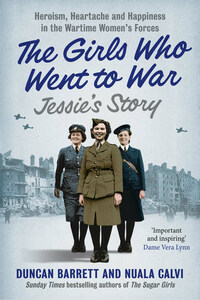

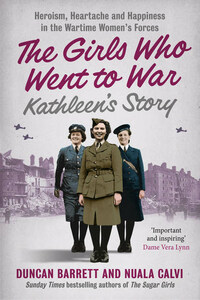

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs (not representations of the women portrayed herein) © George W. Hales/Getty Images (WAAF officer); The Everett Collection/Mary Evans Picture Library (military officer); IWM Collection (WRNS officer); London Fire Brigade/Mary Evans Picture Library (background)

Duncan Barrett and Nuala Calvi assert the moral right

to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007501229

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780007517541

Version: 2015-03-17

In the summer of 1940, Britain stood alone against Germany. One by one, the other Allied nations – France, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Denmark and Poland – had all surrendered, and America and the Soviet Union were yet to join the war. But for all the brave talk of fighting the enemy on the beaches, the country was outgunned – and outmanned as well. The British Army stood at just over one and a half million men, while the Germans had three times that many, plus a population almost twice the size of Britain’s from which to draw new waves of soldiers.

Clearly, in the fight against Hitler, manpower alone wasn’t going to be enough.

During the First World War, all three branches of the British military had formed a female auxiliary service, but the new organisations had been mothballed soon after hostilities came to a close. In the build-up to a second global conflict they were hastily recalled to life, and it was now that the women’s forces really came into their own.

Initially, both the Army and the RAF were supported by the Auxiliary Territorial Service, or ATS, but two months before Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) split off and became a separate organisation. Fulfilling an equivalent role in relation to the Navy was the Women’s Royal Naval Service. Among the women’s forces, the WRNS was considered the ‘senior service’, just as the Navy was among the three male forces. Its members – thanks to its unwieldy acronym – were known as ‘Wrens’.

In fact, settling on a suitable name for the organisation had proved quite a minefield. It came close to being christened the Women’s Auxiliary Naval Corps, until someone realised that the abbreviation ‘WANC’ might provoke jibes from the sailors its members worked alongside.

Of the three services, the WRNS was generally regarded as the classiest, and was by far the hardest to get in to, unless you had the right naval connections. Being a Wren was seen as rather glamorous, in part thanks to the distinctive navy blue uniform, which had been designed by the celebrated couturier Edward Molyneux. While the WAAF and ATS outfits featured belted waists and pleated pockets that were unflattering on the hips, the WRNS jacket was straight and streamlined, and the officer’s tricorne hat was much admired. To top it off, the Navy girls were even allowed to wear black silk stockings – when asked why he had permitted such extravagance, the First Lord of the Admiralty joked, ‘The Wrens like the feel of them, and so do my sailors.’

By the time war was actually declared in September 1939, all three of the women’s services had been deluged with applicants, and tens of thousands of young women were soon donning their distinctive new uniforms – khaki for the ATS, Air Force blue for the WAAF, and navy for the WRNS. When conscription for women was introduced in the National Service Act of 1941, the ranks of the services were swelled further, as many girls chose the rigours of military life over hazardous work in a munitions factory or the hard labour of tilling the fields with the Land Army. There were some who refused to be drafted – 257 female conscientious objectors found themselves imprisoned as a result of their principles – but most girls reported for duty reasonably willingly and did their best to fit into life in the forces, however alien the military environment might seem to them.