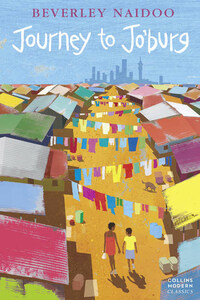

First published in Great Britain by Longman Group Ltd 1985

First published by Collins 1987

This edition published by HarperCollins Childrenâs Books 2016 HarperCollins Childrenâs Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd, 1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Childrenâs Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Beverley Naidoo/Canon Collins Educational Trust for South Africa 1985

Illustration copyright © Lisa Kopper

Note from the author copyright © Beverley Naidoo 1999

Why Youâll Love This Book copyright © Michael Rosen 2008

Journey to Joâburg is published by arrangement with Longman Group Ltd, London

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2016

Cover illustration © Andy Bridge 2016

Beverley Naidoo and Lisa Kopper assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007263509

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780007368853

Version: 2016-07-22

In memory of two small children who died far away from their mother ⦠and to Kentse Mary Sebate, their Mma, who worked in Joâburg.

The history of childrenâs books is full of wonderful and extraordinary stories, but it has to be said that a great majority of these are about one tiny, narrow band of the human race: middle-class western European and American people. Of course, our massively popular folk tales talk of peoples struggling to survive â think Hansel and Gretel, for example â but once novels for children started to be written, the authors tended to write about people like themselves. This is not a complaint â I do it myself! However, when a book comes in front of us that does that rare thing of talking of people with a way of life utterly distant from this western European type, itâs my view that we should celebrate it.

When Beverley Naidoo wrote Journey to Joâburg, South Africa was a place that had a very special kind of political structure:it was ruled by a white elite that had its origins in two countries â Britain and Holland. So, the two languages of those who ruled were English and a form of Dutch called Afrikaans. There was also a big minority of people of Eastern European Jewish origin, they tended to speak English rather than Afrikaans. But the large majority of people living under this rule came from the many nations of Africans â people like the Tswana and the Zulus â who had been living on the continent of Africa long before the British or Dutch had come to settle and rule there. The system of rule was called Apartheid, an Afrikaans word meaning something like âseparatenessâ. However, this makes Apartheid sound as if it was just a matter of living separately; it was far from it. It meant something much more stark and cruel: the white people of European origin were the only ones who benefited from the system. They invented hundreds of rules that tried to ensure that white people and black people were kept apart. This meant that there were many places â like the best swimming pools, shops, schools and colleges â where black people were not allowed to go. But in the end it was Apartheid itself that fell apart! Nelson Mandela who had fought against the system was released from prison and the black people of South Africa won the right to vote.

So, Journey to Joâburg has become a different kind of book. When Beverley wrote it, it was a book that threw light on a problem that was going on at that very moment. I can remember the feeling that teachers, writers and school students had: this was a story about now, and spoke out on behalf of the people suffering in South Africa. We had read, heard or seen musicians, poets and plays that had spoken like this, but we had never thought there could be a childrenâs book that talked of such things. And yet here it was. For some of us who supported Nelson Mandela and what was called the âAnti-Apartheidâ movement, this was very exciting.

Of course, some people said that childrenâs books shouldnât be âpoliticalâ, or that they shouldnât âpreachâ or try to put over a âmessageâ. Well, the only problem with this argument is that one of the most popular childrenâs books, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, is a very political book and does put over a âmessageâ. Whatâs more, all through Victorian times, many, many childrenâs books, comics and magazines put over strong messages about how children should behave. Indeed, lots of popular stories also spoke about how it was right and proper for British people to rule in Africa. So, in some ways, I see Beverleyâs book almost as a reply to those kinds of books and magazine stories that I used to read when I was a boy, books that told me that I was civilised and sensible, and African people were dangerous or childish.