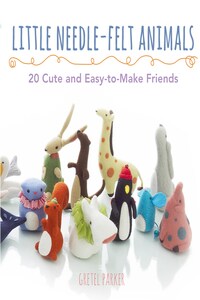

I discovered needle-felting five years ago, when someone sent me a kit as a present. At first I was confused; what was it? How did it work? But from the moment I began stabbing and shaping the wool, I knew that here was my craft. My first piece was a toy rabbit based on one of my own paintings. The delight of making a small creature that could sit in the palm of my hand was captivating, and needle-felting soon became my day job. There is something magical about taking a simple length of wool roving and sculpting it into a three-dimensional form. It’s a craft that doesn’t require you to memorise stitches or use expensive tools. You just pick up a couple of felting needles and begin. It is lap friendly, and the kit is easily carried around.

When I started out, needle-felting was still fairly unknown in the UK, but word has spread and more people are discovering it every day. The patterns in this book range from the very easy to the more challenging, and I hope there is something for everyone to try. I am thrilled to be given this opportunity to share my designs and techniques with a wider audience and hope that it encourages many more people to enjoy this unique and versatile craft.

Needle-felting is so simple – simply grab some wool, your felting mat and a couple of needles (see here) and get stabbing! A few basic techniques are useful to know about before you begin, though, so read on.

How Does Needle-Felting Work?

Wool fibres are covered in small scales and natural oil. The action of continually pushing sharp, barbed needles into it makes it matt together – or ‘felt’. The more the wool is worked, the firmer it becomes. As the air is punched out and the fibres stick together, the volume of the wool decreases dramatically. So although it seems as if you’re starting out with a large amount of material, the finished piece will be about a third of the size of the original mass.

Don’t worry if you make mistakes; they are easily fixed. You can even cut bits off and patch it over as if nothing had happened. Wool is a wonderful, versatile material.

Try to tear your wool apart, rather than cutting. Rough ends meld together far better than cut ones.

Follow the pattern measurements and finished project sizes as closely as possible. However, the measurements are approximations only, so don’t panic if something comes out a centimetre shorter or taller.

There is really only one technique to needle-felting – gently stabbing the wool with one or two needles until it firms up. At first it feels as if you are jabbing at thin air, but after a few minutes you begin to feel some bite. A while later you will hear a quiet scrunching sound, as if you were walking through snow. When you hear this, you know that the wool is getting to the malleable stage, when you can start to shape and sculpt it.

Many of the patterns in this book start in the same way: folding wool over and inserting various sizes of filling. This bulks out the bottom of the animal or bird, making a basic bulb or teardrop shape, which is then developed as the pattern progresses.

Your fingers are the other tool you need for successful shaping. To make thin forms, pinch together the roving as you carefully work with one needle, to fix and solidify the wool. It takes time, but even the skinniest of tails can eventually be made firm.

Several of the designs need a nice flat bottom to sit on. If you hold the body vertically on the felting mat, so that it is already ‘sitting’, you will get a preliminary flat base, which you can then pick up and work on. Using your thumb and index finger as a circular template helps define a neatly curved edge.

Unless you actually want a flat design, turn your project as you work so that you are treating all sides equally. It’s quite tempting sometimes to get so involved with one area that the rest is forgotten, which results in overworked areas. A project is never entirely finished until the final stage, when the fine-tuning takes place. For me, this is the part that takes the most time.