I’m dragging my feet in his wake, doing my best to keep apace with him. For as soon as I slow down, he pulls the chains that are attached to manacles on my wrists and a metal ring around my neck. And if he does it with a jerk, then I’ll keel over right into the muck the road has turned into because of the recent downpour. And I wouldn’t like to stain my new, and so far, the only, clothes I have. Well regardless, this shirt and caftan are much better than the half-rotten rags they raised me from my grave in.

There is a crowd of curious onlookers gathered on the either side of the road. Even though they huddle together, especially when we walk past, they still can’t contain their curiosity – they haven’t ventured out to the middle of nowhere in these small hours for nothing, right? Thick, dark clouds have overcast the autumnal sky and it’s impossible to guess if it’s still morning or if the sun has already started on its way back to the horizon. I can literally feel that nip in the air that signals the upcoming winter. While they were pulling me out of the ground an hour before dawn, I saw my breath escape in tiny clouds of steam and heard the hoarfrost squeaking and crunching underfoot when I stepped onto the grass.

The faces of the people who see me show the whole range of human emotions: from curiosity, to awe, and even terror. But then again, why should I be surprised? I’m sure it’s not every day that they have an opportunity to see a creature from legends and old folk tales raised from the dead. But I have no intention of becoming an exotic beast shown off to entertain the audience, so I lower my head and hope my hood will allow me at least to ignore the prying stares.

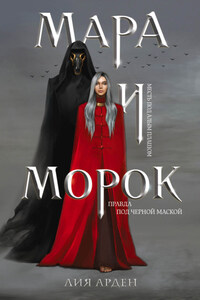

Of course, I couldn’t escape those stares even if I tried. My scarlet cloak is too conspicuous against the pale background. My lips break into a thin smile as I realize they have dressed me in these ritual robes on purpose, to remind people of my origins and what I really am. Yes, my sisters and I used to wear these to stand out against the winter landscapes and snow-white shrouds that our Goddess owned. But now I’m splashing through the mud, leaving stains on the hem of my cloak. It shouldn’t bother me at all but that nagging feeling of resentment has already extended its tentacles and is reaching for my chest.

There were seven of us, including me. Maras. This is the name people gave us. We can do things common people do: drink, sleep, fear, die, and scream with pain. The only difference is that we were all marked by Morana, the Goddess of Death, when we were ten years old, and have been destined to do her bidding ever since. You are special, some people said; your mission means more than life, echoed others while taking us away from our families to bring us up in keeping with their illusory higher cause. I wish they’d repeated that to my sisters, now that their flesh is decomposing in the mass grave. Or they might have been burnt and my body alone had the bad luck of remaining intact.

A while ago they may have been right, we might have been special. But everything’s changed.

I died a long time ago and now the world is a far cry from what it used to be.

He finally tugs at the chain and I stumble forward staining my boots even more. If it were anyone else, I would just hiss my curse and the person would bolt, scared out of their wits and worrying that the few words that have escaped my lips might bring bad luck to his whole kin. But with this man, all I can do is look up in terror and see that black-and-gold mask that hides his whole face, partly covered by the shadow from his hood. The mask reminds me of some beast, probably a jackal, with black holes where the eyes should be. Anyone would wonder if there even is a human being behind the mask. Though whether he is human is also a big question. There’s a rumor that there’s no face at all, just the darkness itself or a bare skull. No one can say for sure as no one has seen it and lived to tell the tale. Creatures like him are called Moroks. They serve the Shadow, which has no beginning and no end. It’s nothing but emptiness, silence and endless loneliness.

I drop my gaze and ask for forgiveness. Then, I awkwardly pull my foot out of the mud with a mortifying squelch, to be able to continue walking. I don’t have the guts to look up at him again but I can feel the pressure of his unwavering stare. Two platoons are accompanying us so as to hold back the crowd and prevent them from getting their hands on me. But it all seems a bit excessive, as no one would approach me, even at knifepoint, while Morok is in the vicinity. If I could, I myself would put as much distance as possible between us.

“How can we be afraid of anyone, we, marked by Morana herself?” I remember asking one of my sisters. Well, somehow, we can.

Absolutely everyone is terrified of Moroks.

And it was a Morok who raised me from the ground three days ago and by enabling me to walk and talk, magically tied me to him. I can breathe only while he is breathing. And it’s only the creatures like him who are capable of such sorcery. No one’s offered me a mirror, so I have no idea how I look, though during the first night I surreptitiously touched my face here and there and didn’t feel anything out of the ordinary, except for the hollow cheeks. While examining the rest of my body I just noticed that my skin had a cadaverous look to it and my long, black hair has turned grey. It doesn’t look silver now, just plain grey, like a mouse’s fur. I look at my hands with disgust: the fingers are too thin, like bones wrapped in a bit of skin, and I dread to think what my face looks like right now. Though people are not scattering away in repulsion, which I take as a good sign.