1. Portrait of Michelangelo, ca. 1533. Black chalk. Teyler Museum, Haarlem.

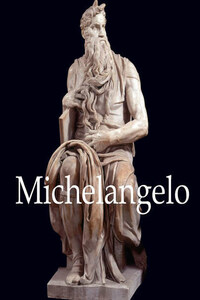

2. Copy of a figure from “Tribute Money” by Masaccio, 1488–1495. Kupferstichkabinett, Munich.

3. Raphael, Leon X, ca. 1517. Distemper on wood, 120 × 156 cm. Uffizi, Florence.

The Brancacci Chapel and Uffizi Gallery in Florence amply illustrate the powerful influence on Michelangelo of his fellow masters. Cimabue’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Eight Angels and Four Prophets and Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna, both at the Uffizi, plus Masaccio’s Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise at the Brancacci, all feed directly into one of the most talented and famous artists of Italy’s sixteenth century.

Up until the fourteenth century, artists ranked as lower-class manual labour. After long years of neglect, Florence began importing Greek painters to reinvigorate painting that had become stuck in a Byzantine style that was stiff, repetitious and top-heavy with gold.

Born in Arezzo, Margaritone was one little-known fourteenth-century painter who broke away from the ‘Greek style’ that permeated painting and mosaics. Though a true pioneer, he is less remembered than Cimabue and Giotto. Also much influenced by Greek painting, Cimabue was a Florentine sculptor and painter who quickly injected brighter, more natural and vivacious colours into his paintings. We are still a long way from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, but painting was now moving in its direction.

No later than the early fourteenth century, Giotto di Bondone had fully emancipated Florentine painting from the Byzantine tradition. This student of Cimabue’s redefined the painting of his era. Between Cimabue’s and Giotto’s works cited above, the new trend stands out in the rendering of the Virgin’s face and clothing. Cimabue was breaking out of the Byzantine mould. In a later work, he would himself come under the influence of one of his own students: Giotto’s Holy Virgin has a very lifelike gaze and cradles her infant in her arms like any normal caring young mother. The other figures in the composition appear less Byzantine and wear gold more sparingly. The pleating on her garb outlines the curves of her body. These features define his contribution to a fourteenth-century revolution in Florentine art. His skills as a portrait and landscape artist served him well when he later became chief architect of the Opera del Duomo in Florence, whose bell tower he started in the Florentine Gothic style. Like Michelangelo after him, he was a man of many talents. The fourteenth century proved most dynamic and Giotto’s style spread wide and far thanks to Bernardo Daddi, Taddeo Gaddi, Andrea di Cione (a.k.a. Orcagna) and other heirs.

4. Cimabue, Madonna in Majesty with Eight Angels and Four Prophets, ca. 1280. Distemper on wood, 385 × 223 cm. Uffizi, Florence.

5. Giotto de Bondone, Madonna Enthroned with Child, Angels and Saints, 1306–1310. Distemper on wood, 325 × 204 cm. Uffizi, Florence.

6. Fra Angelico, Annunciation, 1430–32. San Marco, Florence.

Next came a period of International Gothic influence in the fifteenth century just as Masaccio erupted into the Florentine art scene with his rich intricacies of style. His impact on Michelangelo was to be dramatic. Masaccio’s actual name was Tommaso di Giovanni Cassi; born in 1401, he died after only twenty-seven hyperactive years. He was among the first to be called by his given name, a sure sign of new, higher social status for artists. Two noteworthy works are his Trinity at the Santa Maria Novella and the Expulsion from Paradise in the Brancacci Chapel. This leading revolutionary of Italian Renaissance art upset all the existing rules. Influenced by Giotto, Brunelleschi’s new architectural attitude to perspective, Donatello’s sculpture and other friends or cohorts, Masaccio added perspective into his frescoes alongside those of Brancacci, populated with figures so lifelike the eye almost senses their movements. Masaccio steers attention into exactly what to notice, leaving viewers no leeway for apathy. Expulsion from Paradise is easily his masterpiece: hunched over with sin and guilt, the two figures radiate pure shame and suffering. It is distinctly more terrifying than Masolino’s treatment of the same theme opposite it. Late twentieth-century restoration work on the chapel abolished the fig leaves, bringing all the genitalia back into full view: this was the first nude painting ever and Masaccio was offering art now far removed from anything Byzantine. His painting was so original that Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Caravaggio, Ingrès and Michelangelo himself all went out of their way to see it. Whatever direction their works took, each had his debt to Masaccio.

Masaccio’s legacy is huge. Fra Giovanni da Fiesole (a.k.a. Fra Angelico) came much under his influence, though many years his senior. This pious and humble Dominican friar completed lovely frescoes for the cloisters and cells of the San Marco Convent, including the