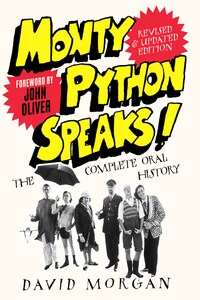

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © David Morgan 2019

Cover design by Paula Russell Szafranski

Cover photograph © Michael Ochs Archives; Shutterstock

David Morgan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008336806

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9780008336813

Version: 2018-12-11

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

FOREWORD BY JOHN OLIVER

INTERVIEWEES

INTRODUCTION

PRE-PYTHON

BIRTH

TAKE-OFF

THE PYTHONS THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

The Control Freak

Splunge!

The Nice One

The Cheeky One

The Zealous Fanatic

The Monosyllabic Minnesota Farm Boy

The Group Dynamic

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY … THE SAME?

FEAR AND LOATHING AT THE BBC

MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL

THE US INVASION BEGINS

THE FOURTH (AND FINAL) SORTIE

CAUGHT IN PYTHON’S ORBIT

LIFE OF BRIAN

FLYING SOLO

THE MEANING OF LIFE

LE MORTE D’ARTHUR

THE ‘IF YOU COULD SAVE ONLY ONE THING YOU’VE PRODUCED’ CHAPTER

TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY PYTHON

SPAMALOT

DÉJÀ REVUE

EXITING THE STAGE

FINAL THOUGHTS

FOOTNOTES

THE PYTHON OEUVRE

SOURCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Writing about the importance of Monty Python is basically pointless. At this point, citing them as an influence is almost redundant. It’s assumed. In fact, from now on it’s probably more efficient to say that comedy writers should have to explicitly state that they don’t owe a significant debt to Monty Python. And if someone does that, they’ll be emphatically wrong.

This strange group of wildly talented, appropriately disrespectful, hugely imaginative, and massively inspirational idiots changed what comedy could be for their generation and for those that followed.

I first discovered Monty Python when I was probably ten years old, and back then it felt like something I shouldn’t be watching. That was already a pretty big appeal. Then I saw Life of Brian in middle school, when a substitute teacher put it on to keep us quiet on a rainy day. I’m not sure he knew exactly what he was showing us, but I’ve always been hugely grateful for the reckless professional mistake he made that day, because I’ve never forgotten how it made me feel.

I think what I’ve always loved about all of Monty Python’s work is that they’ve never been afraid to get into trouble, and Life of Brian is the perfect distillation of that. There was a famous episode of a BBC talk show back in 1979, when John Cleese and Michael Palin were being interviewed alongside the Bishop of Southwark and a writer called Malcom Muggeridge, both of whom were furious about the film. Incidentally, the very name ‘Malcolm Muggeridge’ is so stereotypically English, it’s almost racist. It’s the name of someone who should be looking after the owls at Hogwarts. Anyway, for twenty minutes, Muggeridge told them off like a pair of naughty schoolboys, calling what they’d done a ‘miserable little film,’ ‘a squalid number’ and ‘tenth rate,’ and said it contained laughs that were ‘rather easily procured.’

And while everything he said was titanic nonsense, it was that last part that drove me crazy. Because nothing about what Monty Python did was easy – not their TV show, not their albums, and certainly not Life of Brian. It’s fucking hard to write such incredibly smart, incredibly stupid comedy.

I got to interview all the Pythons after a screening in New York a few years ago. It was total, beautiful chaos. The audience seemed to turn up in reverence of them, but you’re not going to find a group of people less interested in hearing how important they are. So, they took it in turns to try and create mayhem – turning their chairs the wrong way around, walking off stage when they got bored, and sitting with the microphones in their mouths. They treated the evening, each other, and their own legacy terribly, and it felt like a far more meaningful tribute.

That’s why one of the greatest acts of love I’ve seen was the funeral for Graham Chapman. It was a de facto roast. They saw him off in the spirit he would have wanted, with no respect whatsoever. Here’s what John Cleese said about one of his best friends: