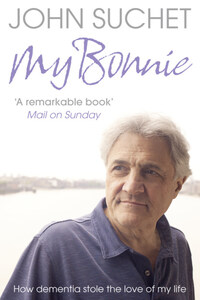

In the summer of 2004, my wife Bonnie and I were in the departure lounge at Stansted airport, waiting to board the short flight down to our house in the French countryside. Bon said she would just nip to the toilet. ‘Fine,’ I said, ‘but don’t be too long. We’ll be boarding soon.’ She walked off to the ladies, which was not more than 10 metres away.

Five minutes went by, 10, then 15. I was beginning to get seriously concerned. Mild worry turned into panic. I looked long and hard at the entrance to the ladies. I decided I would ask the next woman who emerged to go back in and call Bonnie’s name. I imagined the worst, as you do. A heart attack, a stroke, and…No, it didn’t bear thinking about.

A woman came out. It wasn’t Bonnie. I began to move towards her, when suddenly I heard, clear as a bell and reverberating from wall to wall, ‘Would Mr Suchet, Mr John Suchet, please come to the information desk?’

I saw a hundred, no a thousand—make that a million—faces turn towards me. (It was probably about six, but it felt like a million.) I hurried to the desk, expecting to find police, paramedics, who knew what else? My breathing was quick and shallow and I felt nausea in my stomach.

Suddenly there she was. Bonnie. Standing at the information desk, looking totally fine. The panic turned in an instant into relief—and a dose of anger. What on earth was she thinking of? Why in heaven’s name had she come to the information desk, when I was waiting just a few yards away?

But then she saw me, and her face lit up with a beatific smile, which spelled relief from ear to ear. ‘There you are! Thank goodness! I thought I had lost you!’ she said.

I took her by the arm and led her, perhaps a touch too firmly, back to the gate, trying at the same time to work out how she had managed to get past without me seeing her. Then I remembered there were two exits, one on the other side.

‘What was all that about? Why did you have me paged? I was waiting for you right here.’ There was anger in my voice, and I couldn’t disguise it. I looked at her, and she was frowning, but it was not a frown of annoyance—it was a frown of non-comprehension. ‘I don’t understand,’ she said. That struck me as odd. It’s not what you would expect her to say. ‘Don’t be angry…I made a mistake, that’s all. Let it go, please.’ Anything like that would be the normal response. But ‘I don’t understand’—that’s not what you’d expect.

I said nothing more. We boarded the plane. I sat back in the seat and thought the whole incident through. I couldn’t make sense of it. All I knew, deep down, was that it shouldn’t have happened.

We got to France and I quickly forgot about it. I shouldn’t have. It was the beginning.

27th April 1983

Bonnie and I are going to be together at last. I was up at dawn, tidying the bedsit of which I am so irrationally proud. We both had large houses in the English countryside, but I think I love this bedsit more than anywhere I have ever lived. Before breakfast I polished the kitchen and bathroom floors on my knees, then vacuumed the rugs in the main room. After breakfast I went out to the florist and bought some flowers. I didn’t know what to get. The girl said, May I ask what they are for? I grinned from ear to ear. To welcome someone very special, er, a woman. She smiled knowingly and selected something. I can’t remember what she chose. As I left the shop, clutching the bouquet awkwardly, I realised I had nothing to put it in. I went back in. She laughed. I bought a small green vase, pinched at the middle, with slanted ripples in the glass. It is on the sideboard and I am looking at it now as I write this, 26 years later.

I drive to Baltimore Washington International airport in the office Volvo, cursing the traffic that has made me a little late. I park and run towards the arrivals terminal, praying she has not come through. I don’t see her at first, then I realise it is her. A slim figure standing outside the doors. She is wearing a long summer skirt and coloured short-sleeved top. She has her hand on the extended handle of a suitcase. On top of the suitcase is an open wicker bag. Then I realise why I hadn’t at first recognised her. On her head she is wearing a straw hat. Round it are large multi-coloured paper flowers. The hat has cast her face into shadow.

I stop and look at her. She seems so frail. She has lost weight. Those wonderful high cheekbones give her face a fragile beauty. My breath quickens and my heart beats more strongly. My Bonnie is here. She has come to live with me. Her smile when she sees me is nervous, but it lights up her face.

In the car we are silent. I turn to her a couple of times. Each time she returns my smile, but I can sense the anxiety. Why are you anxious? I ask, cursing myself for the stupid question. I’m just a bit nervous, she says. I try to comfort her with a smile.