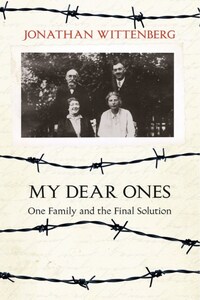

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Jonathan Wittenberg, 2016

Cover photograph © Jonathan Wittenberg

Jonathan Wittenberg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 978-0-00-815803-3

Ebook Edition © May 2016 ISBN: 9780008158057

Version: 2017-05-03

This book is dedicated to my father Adi Wittenberg and to the memory of all the members of his family who perished;

To Daniella Nechama Moffson, daughter of Sheera and Michael, great-great-granddaughter of the quiet heroine of this book;

To my friend David Cesarani without whose encouragement the work would never have been written;

To my wife Nicky and our children Mossy, Libbi and Kadya;

And to the future of all children, especially those who have experienced the fate of the refugee.

My father’s family had felt at home in Germany. They were leaders in the highly cultured world of German Jewry. They fought on the German side in the First World War; my grandfather’s brother was welcomed home to great acclaim as a hero twice-wounded. They spoke German, wrote in German and baked kosher cakes according to German recipes. ‘You have good family connections,’ my father told me. His mother’s father was a world-famous authority on Jewish law, from a dynasty of rabbis.

In 1945 all that was left of my father’s family in Europe were scattered ashes, one grave, their former homes, of which the surviving members were never able to regain possession, and memories. ‘So that you will know where to look for us afterwards,’ his aunt Sophie had written in a final letter informing her brother of her impending deportation. But in her case, and that of her sister Trude and their families, there was no one left for their relatives to find.

‘At first they did it all within the sanction of legality,’ my father used to say. Step by step, in small measures which initially sometimes showed little of outright violence, the Nazis and their supporters removed the Jewish populations in their midst from their positions, hemmed them in with restrictions, laid claim to their belongings, stripped them of their savings, dispossessed them of their homes, isolated them from those they loved, starved and tortured them, robbed them of their lives and turned them into ashes.

Of course I knew as I was growing up that my father’s family had come from Germany and that they had fled when he was in his teens. But I didn’t understand about his part of the family in the same way as I knew the story on my mother’s side. Her parents, also refugees from Germany, lived around the corner and I saw them several times each week. My father’s relatives resided in faraway Jerusalem; his father had died even before my older brother was born, and I had met his mother only two or three times, on her occasional trips to London. She had struck me as generous, gentle and kind, but quiet and self-contained. It never occurred to me, a teenager absorbed in my own life, that it could be important to traverse her quietness and listen to who she was. She used to send us big wooden cases of oranges or grapefruits, an exciting treat from an Israel which I had never yet visited.

I knew, but I didn’t really know; perhaps it would be more honest to say that I didn’t pay sufficient attention or care. There are many things of which one is aware, but only at the periphery of the mind. They never properly penetrate the consciousness, but hover like a distant landscape beyond the parameters of one’s immediate concerns. It doesn’t occur to one to ask the important questions; nothing provokes one to enquire. Only after it is too late is one overcome by a compelling urgency, and in retrospect the failure to have shown sufficient curiosity while there was still time seems as inexplicable as it feels inexcusable: why did I never trouble to ask, before those who could have answered were all dead?