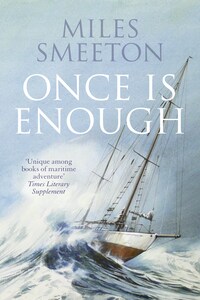

Title Page

Dedication

FOREWORD BY NEVIL SHUTE

1 PREPARATIONS IN MELBOURNE

2 FALSE START

3 THROUGH THE BASS STRAIT

4 ACROSS THE SOUTH TASMAN

5 INTO THE SOUTHERN OCEAN

6 THE WAY OF A SHIP

7 THIS IS SURVIVAL TRAINING!

8 RECOVERY

9 THE TREK NORTH

10 FIRST DAYS IN CHILE

11 REPAIRS IN TALCAHUANO

12 STILL IN TALCAHUANO

13 TO CORONEL AGAIN

14 NOT AGAIN!

15 THERE’S A WIND FROM THE SOUTH

EPILOGUE

APPENDIX: MANAGEMENT IN HEAVY WEATHER

POSTSCRIPT

Copyright

About the Publisher

SOME years ago I had an afternoon to spare in Vancouver, so I went down to the yacht harbour to see what sort of vessels Canadian yachtsmen use. There I found Tzu Hang moored alongside a pontoon, slightly weather-beaten, sporting baggywrinkle on her runners, and wearing the red ensign. As I inspected her Miles Smeeton came up from below and invited me on board. That was my first meeting with this remarkable man; I did not meet his more remarkable wife till some time later.

The Smeetons had bought Tzu Hang in England a year or so previously and they had sailed her out from England across the Atlantic and through the Panama Canal to Vancouver with their eleven-year-old daughter as the third member of the crew. Before buying this considerable ship they had never sailed a boat or cruised in any yacht. They made one trip in her to Holland and then set out across the Atlantic for the West Indies. Navigation was child’s play to them; seamanship they picked up as they went along. With only two adults on board they had to keep watch and watch, but did not seem to find it unduly tiring. They made their landfalls accurately, passed the Panama, reached out a thousand miles into the Pacific before they could lie a course for Vancouver, and they arrived without incident. I asked if they had had any trouble on the way. Miles told me that they had been hove to for three days in the Atlantic; the only trouble that they had in that three days was in keeping their small daughter at her lessons. They made her do three hours school work each morning, all the way.

When I began yacht cruising after the First World War it was regarded as an axiom amongst yachtsmen that a small sailing vessel, properly handled, is safe in any deep-water sea. I think that Claude Worth, the father of modern yachting, may have been partly responsible for this idea, and it may well be true for the waters in which he sailed. A small yacht, we said, will ride easily over and amongst great waves if she is hove to or allowed to drift broadside under bare poles; you have only to watch a seagull riding out a storm upon the water, we said. Perhaps we failed to notice that the seagull spreads its wings now and again to get out of trouble; perhaps we were seldom caught out in winds of force 7 or 8 and much too busy then to observe the habits of seabirds, which probably had too much sense to be there anyway.

From time to time our complacent sense of security was just a little ruffled. Erling Tambs, in Teddy, was overwhelmed in some way by the sea when running in the Atlantic; his account was not very clear and it was easy for us to assume that he had been carrying too much sail, had been pooped and broached to. The lesson to us seemed obvious; heave to in good time or lie to a sea-anchor, perhaps by the stern if the ship was suitable. Captain Voss, sailing with two friends in a seven tonner in the China Sea, was turned completely upside down so that the cabin stove broke loose and left its imprint on the deckhead above, on the cabin ceiling. But that was a long way away; all sorts of things happen in China. … Captain Slocum was lost in the Atlantic without trace after sailing single-handed round the world—but anything could have happened to him.

It has been left to Miles Smeeton in this book to tell us in clear and simple language just where the limits of safety lie. We now know with certainty that the seagull parallel was wrong. A small yacht, well found, well equipped, and beautifully handled, can be overwhelmed by the sea when running under bare poles dragging a warp, or when lying sideways to the sea hove to under bare poles. The Smeetons have proved it, twice. Twice these amazing people saved their waterlogged, dismasted ship by their sheer competence and sailed her safely in to port, greatly assisted on the first occasion by John Guzzwell. With equal competence they have now produced this lucid and well-written book to tell us all about it.