Copyright

First published in 1998 by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

© Sharon Finmark 1998

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Editor: Hazel Harrison

Photographer: Laura Wickenden

Sharon Finmark asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN 9780004133089

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2015 ISBN: 9780008139346

Version: 2015-04-08

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication

Thank you to Madeline and Gary for all their help.

Drying, pastel, 55.5 Ã 40.5 cm (22 Ã 16 in)

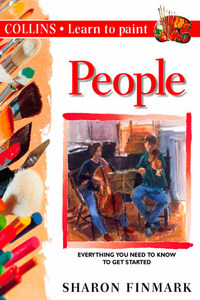

Portrait of the Artist

Sharon Finmark in her London studio.

Sharon Finmark was born and brought up in London, where she still lives, although she has travelled and painted widely in Europe and Canada.

She trained as an illustrator, having abandoned an art-school fine-art course because she wanted to work figuratively â a style of painting perceived to be unfashionable at that time. From 1973 to 1976 she was primarily employed in this capacity, working in a wide range of media from national newspapers and magazines, book publishers and fine-art card makers. She still accepts commissions for illustrative work, but now concentrates most of her energies on her own painting, and on teaching. Since 1980 she has been increasingly employed as a visiting lecturer, giving short courses on painting and drawing in various institutions in England and Canada.

Grove End House

pastel

61 Ã 86 cm (24 Ã 34 in)

She paints a wide range of subjects, in all the media, though is best known for her work in watercolour, pastel and acrylic. Sharon has always been interested in the figure in context, even as a student at college, when representational work was considered old-fashioned. She persevered with her favourite subject and now likes to be considered a visual recorder of people, both public and private.

Girl in Bathroom

pastel

86 Ã 61 cm (34 Ã 24 in)

Why Paint People?

Many amateur artists shy away from human subjects, concentrating on static ones such as still life and landscape. There is a feeling that painting people is too difficult, but I would like to explode the theory that it requires a lifetimeâs drawing experience. To be a successful portrait painter you undoubtedly do need good drawing skills, but I am not dealing with portraiture in this book, but rather on the idea of using figures as an element in your paintings so that they present a more truthful record of the world around you. We live in a densely populated world, and it is a pity to exclude humanity, in all its fascinating variety, from your artistic repertoire. Personally, I find figure work one of the most exciting and rewarding of all painting subjects, and I am sure that you will too, once you have overcome any initial fears.

Chatting

watercolour and gouache

30.5 Ã 40.5 cm (12 Ã 16 in)

In outdoor scenes, a figure or group of figures can provide a focal point for your picture, add atmosphere or even hint at a story, for example a solitary walker on a windswept beach or children playing in a park. In interiors, the presence of people is as natural as that of the furniture made to accommodate them â you would not express the ambience of a pub or café if you were to paint them empty.

People are certainly trickier to draw and paint than still life objects, both because they are complex in themselves and because they seldom remain still, but as long as you observe the overall shapes and proportions, gestures and movements, your approach can be quite loose and sketchy and still make visual sense. In many of the paintings shown in this book, I have aimed at impressions rather than detailed literal descriptions, which can often be more effective and evocative.