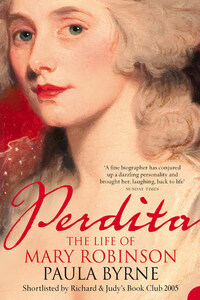

I was delighted at the Play last Night, and was extremely moved by two scenes in it, especially as I was particularly interested in the appearance of the most beautiful Woman, that ever I beheld, who acted with such delicacy that she drew tears from my eyes.

(George, Prince of Wales)

There is not a woman in England so much talked of and so little known as Mrs Robinson.

(Morning Herald, 23 April 1784)

I was well acquainted with the late ingenious Mary Robinson, once the beautiful Perdita ⦠the most interesting woman of her age.

(Sir Richard Phillips, publisher)

She is a woman of undoubted Genius ⦠I never knew a human Being with so full a mind â bad, good, and indifferent, I grant you, but full, and overflowing.

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge)

I am allowed the power of changing my form, as suits the observation of the moment.

(Mary Robinson, writing as âThe Sylphidâ)

In the middle of a summer night in 1783 a young woman set off from London along the Dover road in pursuit of her lover. She had waited for him all evening in her private box at the Opera House. When he failed to appear, she sent her footman to his favourite haunts: the notorious gaming clubs Brooksâs and Weltjeâs; the homes of his friends, the Prince of Wales, Charles James Fox, and Lord Malden. At 2 a.m. she heard the news that he had left for the Continent to escape his debtors. In a moment of panic and desperation, she hired a post chaise and ordered it to be driven to Dover. This decision was to have the most profound consequences for the woman famous and infamous in London society as âPerditaâ.

In the course of the carriage ride she suffered a medical misadventure.>* And she did not meet her lover at Dover: he had sailed from Southampton. Her life would never be the same again.

Born Mary Darby, she had been a teenage bride. As a young mother she was forced to live in debtorsâ prison. But then, under her married name of Mary Robinson, she had been taken up by David Garrick, the greatest actor of the age, and had herself become a celebrated actress at Drury Lane. Many regarded her as the most beautiful woman in England. The young Prince of Wales â who would later become Prince Regent and then King George IV â had seen her in the part of Perdita and started sending her love letters signed âFlorizelâ. She held the dubious honour of being the first of his many mistresses.

In an age when most women were confined to the domestic sphere, Mary was a public face. She was gazed at on the stage and she gazed back from the walls of the Royal Academy and the studios of the men who painted her, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was to painting what Garrick was to theatre. The royal love affair also brought her image to the eighteenth-century equivalent of the television screen: the caricatures displayed in print-shop windows. Her notoriety increased when she became a prominent political campaigner. In quick succession, she was the mistress of Charles James Fox, the most charismatic politician of the age, and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, known as âButcherâ Tarleton because of his exploits in the American War of Independence. The prince, the politician, the action hero: it is no wonder that she was the embodiment of â the word was much used at the time, not least by Mary herself â âcelebrityâ.

Her body was her greatest asset. When she came back from Paris with a new style of dress, everyone in the fashionable world wanted one like it. When she went shopping, she caused a traffic jam. What was she to do when that body was no longer admired and desired?

Fortunately, she had another asset: her voice. Whilst still a teenager, she had become a published poet. Because of her stage career, she had an intimate knowledge of Shakespeareâs language â and the ability to speak it. So, as her health gradually improved, she remade herself as a professional author. Having transformed herself from actress to author, she went on to experiment with a huge range of written voices, as is apparent from the variety of pseudonyms under which she wrote: Horace Juvenal, Tabitha Bramble, Laura Maria, Sappho, Anne Frances Randall. She completed seven novels (the first of them a runaway bestseller), two political tracts, several essays, two plays and literally hundreds of poems.