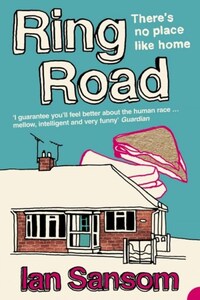

Containing the customary avowals, apologies, concealments of artistry, confidences, explanations and precepts, and a note on the tipping of winks

I worked on a farm once, when I was first married, in County Antrim, and one of the men I worked with had been in London doing the roads, during the early Seventies, at the beginning of the Troubles, and he claimed that things were so bad in those days that he would post ham in an envelope back home to his family in Belfast. I was never sure if he was having me on or not – it’s always difficult to tune in to another nation’s sense of humour, and I was an Englishman abroad – but I always thought it was a nice idea, and I like to think of this book as similar in some way, as the equivalent of some ham in an envelope, posted in reverse, from me here to you elsewhere, wherever you are. It’s probably like ham in other ways too, some people would say.

When I published my first book, The Truth about Babies (Granta, 2002), my wife said she’d only read the next one if I managed to make no mention of vomit, diarrhoea, urine, sperm and other bodily fluids, and I’ve done my best, although she may wish to skip a few pages… The index is designed for those with similar aversions or inclinations.

When I sent my mum a copy of the baby book she said, ‘That’s nice, dear,’ which is pretty much what she’s said to me since I first brought drawings home from school, and which still seems to me about the right response to anyone claiming to be an artist. These days, reticence is easily underrated. But then so is enthusiasm. When we were growing up my mum and dad provided for us children, they cooked good food for us to eat, they made sure we brushed our teeth and were polite, and didn’t watch too much television, they taught us how to make our own beds, helped us with our homework and pointed out interesting things when we were on long car journeys. Perhaps this last explains the footnotes.

The rest of the mechanics of the book are obvious, I hope, and require no further admissions or explanation. (Apart, perhaps, from the brief chapter summaries and epigraphs, which seem to me a mere practical courtesy but which I’m aware are currently out of fashion, and so may seem avowed and unusual rather than commonsensical or natural, like wearing spats, or clogs, or a smock. But fashions come and go – maybe if you keep the book in a cupboard in a few years’ time it’ll all be back in again.)

Writers are, of course, wilful and selfish individuals who only get away with writing because other people allow them the privilege, but I know from long experience that listening to writers saying their thank yous is a bit like listening to people pray or talking about sex – it’s not necessarily unpleasant and everyone does it sometimes, but you do wonder if maybe they could learn to do it in their own heads and in the privacy of their own homes. So I have left all my acknowledgements until the end. They are an apology as much as an explanation.

Anyway, I do hope you enjoy the book – it’s meant for you to enjoy. It would be presumptuous of me to say what it’s all about, or even to pretend that I know, although maybe you’ll understand if I say that as a child on summer evenings, on Sundays, our parents would often have relatives over for tea – this was before barbecues had arrived and when family lived close by – and my aunts and uncles would come and we would sit around the dining table, which now serves me as a desk, and we would eat sandwiches and salads, and we would talk and play games, and I would fight with my cousins, and I can remember that I was amazed that these people were supposed to be my relatives, people with whom I seemed to have nothing whatsoever in common. It was a long and painful lesson, undiminished even by crab paste and trifle, and I thought it would be good to write a book that somehow reflected those Sunday teatimes, and which would remind me of the many different ways in which people live their lives, which is what makes our lives possible.

It would be self-serving of me to say anything else, except perhaps that the town is not meant to be a replica of any particular place, although I believe it does exist, and that I’ve never met any of the people, although there are equivalents, and that each chapter can be read on its own as well as in relation to all the others, although I hope, of course, that you’ll read them all. There are no themes that I’m aware of and any obscurities are unintentional.