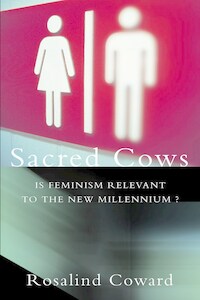

Sacred Cows: Is Feminism Relevant to the New Millennium?

The women’s movement has transformed British society since the 1960s. In this contentious and controversial book leading feminist writer Ros Coward asks, is it now holding us back?When women set out to change the world and their place in it in the 1960s and 1970s it seemed they had a long struggle ahead. Educational standards for girls were lower, they were not expected to take on serious jobs, women did not get paid as much as men in identical jobs, they were not given maternity provision (not least because they were not expected to work after getting married, let alone having children). Women’s health was not researched as thoroughly as men’s, there were few women doctors, politicians, senior managers…Within a generation, our world has been transformed into one in which women are assumed to be the equals of men. Indeed, many feminists continue to argue that women are superior to men. But in a world in which girls consistently attain better exam results than boys, achieve a higher percentage of university places, are more likely to get jobs and whose expectations – of flexible working lives – are more attuned to the needs of the modern workplace, such a suggestion seems as discriminatory as the world of the 1960s was to women.In this controversial, hard-hitting and myth-debunking book, Ros Coward looks at feminism’s achievements and asks that most un-PC of questions: do we need feminism any more? Or is it damaging of real relations between men and women, demonizing men and denying them the right to understanding and equality in a world that is harsher for them than ever before?