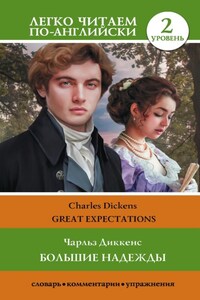

Do you know what it is to be poor? Not poor with the arrogant poverty – certain people complain of who have five or six thousand a year to live upon; who yet swear they can hardly manage to make both ends meet. I mean really poor – downright, cruelly, hideously poor, with a poverty that is graceless, sordid and miserable. Poverty that compels you to dress in your one suit of clothes till it is worn threadbare. That denies you clean linen on account of the ruinous charges of washerwomen[1]. That robs you of your own self-respect, and causes you to slink along the streets vaguely abashed, instead of walking erect among your friends in independent ease. This is the sort of poverty I mean. This is the curse; this is the moral cancer that eats into the heart of any human creature and makes him envious and malignant. When he sees the fat idle woman passing by in her luxurious carriage, lolling back lazily, when he observes the brainless and sensual man smoking and dawdling away the hours in the Park, then the blood in him turns to gall, and his suffering spirit rises in fierce rebellion, crying out,

“Why in God’s name, should this injustice be? Why should a worthless lounger have his pockets full of gold by chance and heritage, while I, toiling wearily from morning till midnight, can scarce afford myself a satisfying meal?”

Why indeed? I have often thought about it. Now however I believe I can solve the problem out of my own personal experience. But… such an experience! Who will believe that anything so strange and terrific ever chanced to a mortal man? No one. Yet it is true; truer than so-called[2] truth. Moreover I know that many men are living under the same influence, that they are in the tangles of sin, but too weak to break the net in which they have become voluntarily imprisoned. Will they be taught, I wonder, the lesson I have learned?

But I do not write with any hope of either persuading or enlightening my fellow-men[3]. I know their obstinacy too well. I can gauge it by my own. I used to have proud belief in myself. And I am aware that others are in similar case. I merely intend to relate the various incidents of my life.

During a certain bitter winter, when a great wave of intense cold spread throughout all Europe, I, Geoffrey Tempest, was alone in London and starving. Now a starving man seldom gets the sympathy he merits. Few people believe in him. Worthy folks are the most incredulous. Some of them even laugh when told of hungry people. Or they will idly murmur ‘How dreadful!’ and at once turn to the discussion of the latest news for killing time. To be hungry sounds coarse and vulgar, and is not a topic for polite society, which always eats more than sufficient for its needs.

That time I knew the cruel meaning of the word “hunger” too well: the gnawing pain, the sick faintness, the deadly stupor, the insatiable animal craving for mere food. I felt that I had not deserved to suffer the wretchedness in which I found myself[4]. I had worked hard. From the time my father died, when I discovered that every penny of the fortune went to the swarming creditors, and that nothing of all our house and estate was left to me except a jewelled miniature of my mother who had lost her own life in giving me birth, – from that time, I had toiled late and early. I had used my University education to the literature. I had sought for employment on almost every journal in London, – refused by many, taken on trial by some, but getting steady pay from none.

Whoever seeks to live by brain and pen alone is, at the beginning of such a career, treated as a sort of social pariah. Nobody wants him, everybody despises him. His efforts are derided, his manuscripts are flung back to him unread. He is less cared for[5] than the condemned murderer in gaol. The murderer is at least fed and clothed. A clergyman visits him, and his gaoler will occasionally play cards with him. But a man with original thoughts and the power of expressing them, appears to be regarded by everyone in authority as much worse than the worst criminal.

I took both kicks and blows in sullen silence and lived on, – not for the love of life, but simply because I scorned the cowardice of self-destruction. I was young enough not to part with hope too easily. For about six months I got some work on a well-known literary journal. Thirty novels a week were sent to me to ‘criticise’. I was glancing hastily at about eight or ten of them, and writing one column of abuse concerning these thus casually selected. The remainder were useless at all. I found that this mode of action was considered ‘smart,’ and I pleased my editor who paid me the munificent sum of fifteen shillings for my weekly labour.

But on one fatal occasion I changed my tactics and warmly praised a work which my own conscience told me was both original and excellent. The author of it was an old enemy of the proprietor of the journal on which I was employed. My eulogistic review, unfortunately for me, appeared, and I was immediately dismissed.