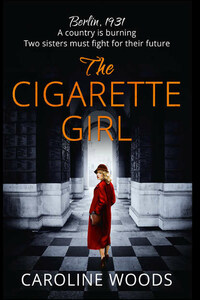

BERLIN, 1931: Sisters raised in a Catholic orphanage, Berni and Grete Metzger are each other’s whole world. That is, until life propels them to opposite sides of seedy, splendid, and violent Weimar Berlin.

Berni becomes a cigarette girl, a denizen of the cabaret scene alongside her transgender best friend Anita, who is considering a risky gender reassignment surgery. Meanwhile Grete is hired as a maid to a Nazi family, and begins to form a complicated bond with their son whilst training as a nurse.

As Germany barrels toward the Third Reich and ruin, both sisters eventually come to the same conclusion: they have to leave the country. And they will leave together. But nothing goes as planned as the sisters each make decisions that will change their lives, and their relationship, forever.

SOUTH CAROLINA, 1970: With the recent death of her father, Janeen Moore yearns to know more about her family history, especially the closely guarded story of her mother’s youth in Germany. One day she intercepts a letter intended for her mother: a confession written by a German woman, a plea for forgiveness. What role does Janeen’s mother play in this story, and why does she seem so distressed by recent news that a former SS officer has resurfaced in America?

At St. Luisa’s Home for Girls in western Berlin, birthdays were observed, not celebrated. Berni’s eighth, which fell in the winter of 1923, came and went with neither singing nor candles on a wooden Geburtstagskranz.Instead, the nuns burned money.

“They treat us like livestock,” Berni hissed into her little sister’s good ear that morning at breakfast. They were eating dry slices of Vollkornbrot with nothing to improve its taste: no meat, no butter, no jam. “Kannst du mich hören?” This was Grete’s least favorite question, but Berni could never help asking.

Grete, who was five, tugged a lock of blond hair over her left ear. It was smooth and pink as a shell, with fewer grooves in it than in other ears. “I can hear you,” she muttered with a glance at the sisters’ table. “You needn’t speak so loudly.”

Berni took a bite of bread and wrinkled her nose, tasting a distinctive tinge of fish. On Friday mornings, the stink of pickled herring seeped into everything in the refectory: the girls’ hair, their bread, their thin gray dirndls. Having served breakfast, the cook and her staff peeled open tins of Voelker’s fillets to prepare a meatless dinner of herring salad. The one aroma that could cut through the fishy air was the comforting smoke from burning pine logs. But that winter the stack of firewood in the circular rack had dwindled.

“If we had parents,” Berni said, mouth full, “we’d be eating jam, cookies, tea—”

“Hush,” whispered Konstanz, who sat on Berni’s left. “I have a father, and he always said children need nothing more than potatoes to survive.”

“I am sure he didn’t serve you frozen milk.” Berni tilted her cup and glared at the sisters, who ate knackwurst and drank coffee at an elevated table, their faces hidden by the lily petals of their cornets. They didn’t seem even to notice that today, for the first time, there was no fire at all. For firewood you needed money, and the sisters’ money, it seemed, was no longer any good.

Each Friday the firewood man arrived just after morning prayers, when the girls had their hands folded in their laps, their eyes active. Sister Maria Eberhardt, the reverend mother, waited for him beside the back door of the refectory with an envelope of cash.

Over the course of the winter, the envelope had grown larger and larger. On the first of the new year, Sister Maria paid him with a box full of money. Then a basket. Berni had heard the term “inflation,” but she didn’t understand what it meant or why it happened. She didn’t yet know that panic and hysteria were driving Berliners to vice, to risk. Her world was still small; what she knew was the slap of a bleach-dipped rag against the bathroom floor, the chill of chapel marble under her knees. From history class, she knew there had been a Kaiser and now there was a democracy, but as a Catholic—a minority in Berlin—she should not forget the pope sat above everyone else.