He woke with a sense of shock. He had no idea who he was. Or where he was. Or who this woman was, sleeping so peacefully beside him.

Oh God. Did he want to know who he was? Would it be an unpleasant surprise?

Later, when he told his doctor, he would estimate that this blankness, this disorientation, this absence of self, probably lasted less than a minute, maybe not even thirty seconds. At the time it seemed like an age.

What he also realized later – and this he didn’t tell his doctor, couldn’t tell his doctor, couldn’t tell another human being ever – was that he had experienced, in that brief moment, the first intimation of doubt. To most of us, plagued as we are by doubt, this may seem incredible, but men like this man – I feel it would be impolite, in a curious way, to give you his name before he himself has remembered it – manage to live without feeling any doubt at all, do things that would be impossible if they felt even a shred of doubt. Garibaldi, Hitler, Colonel Gaddafi, could they have done what they did if they’d had doubts? Not that I am putting our still unnamed hero in that category.

He felt something that he had not felt in his life for a very long time – real alarm. This was extremely disconcerting. He was always so completely in command of himself, prided himself on not needing an alarm clock because his body did what he told it to do; he was always in control, people thought him a control freak.

Well, that was something. That was a piece of knowledge about himself. He was a control freak. But today he was a control freak out of control. He was breaking into a sweat, he could feel the wetness of panic all over his skin.

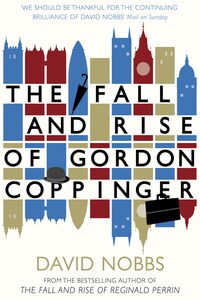

Memory came back to him in small bits. Somebody calling him Gordon. He was Gordon somebody. This narrowed it down, but it really didn’t help all that much. Then from nowhere, in the utter darkness of the bedroom, there flashed into his mind a vivid memory of Mr Forbes-Harrison, his maths teacher, calling out, in a grim yard behind a grim school on a grim, grey morning, ‘You, Coppinger, where do you think you’re going?’ to which he had replied, to his own astonishment, as well as Mr Forbes-Harrison’s, ‘To the very top, sir.’

And with that ‘sir’ there came the thought that he hadn’t called anybody ‘sir’ for a very long time. People called him ‘sir’ now. He wasn’t just Gordon Coppinger. He was Sir Gordon Coppinger.

Now complete awareness flooded in, astonishing him. He was a great man and a rich one. He was a financier and an industrialist with a finger in many pies, ‘not all of which are steak and kidney’, as he used to say only too often, to prove that he still had a sense of humour, though many people thought it proved that he hadn’t. He owned the twenty-six-storey Coppinger Tower in Canary Wharf. In his huge and luxurious yacht, the Lady Christina, based in Cannes, he gave holidays every summer to men of power and influence.

He was a patriot and a philanthropist. He had created the Sir Gordon Coppinger Charitable Foundation, which supported many good causes. He owned the Coppinger Collection, which housed many masterpieces. The football team that he owned played at the Coppinger Stadium. It was time to get up.

Or was it? Not quite yet, perhaps. He knew who he was now, but he still wasn’t sure where he was. The darkness in the room was absolute, which suggested that he was at home, in the vast master bedroom, with its thick gold curtains and its thermal blinds. But suggestion wasn’t enough. He needed to know.