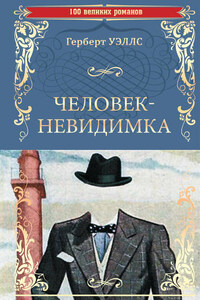

Herbert George Wells (H.G. Wells, 1866–1946), the famous English novelist, is best known for his science fiction novels, such as The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and comic books Tono-Bungay (1909) and The History of Mr. Polly (1910). Wells was not only a writer of rich imagination and extraordinary ideas, but a journalist and a sociologist.

Despite the constant threat of poverty in his youth, Wells won a scholarship to study biology at the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College in London) and in 1888 graduated from London University to become a science teacher. His early masterpieces of science fiction combine fantasy, science and reality.

Wells was a socialist by his convictions, and in his works he treated people from unprivileged backgrounds with great sympathy and understanding. They do not have the false sense of superiority that Griffin or Dr. Kemp have in the novel The Invisible Man. This novel about an ambitious young scientist has unexpected plot twists and poses many moral questions to readers. It is not surprising that it has been enormously popular among them for more than 100 years.

Before you start reading the first chapter of the novel, answer the following questions:

What role does science play in the lives of each of us?

Do scientific discoveries imply benefits or losses for society? Do you agree that scientific research should be controlled and, if necessary, limited to avoid threats to mankind?

How does the scientist's personality influence his career?

Does a scientist need such traits as honesty, responsibility and integrity?

What moral choices does a scientist often face?

Сhapter 1

The Strange Man's Arrival

The stranger came early in February, one winter day, through a biting wind and heavy snow. He walked from Bramblehurst railway station, carrying a little black portmanteau in his gloved hand. He was wrapped up from head to foot, and his soft felt hat hid every inch of his face but the shiny tip of his nose. The snow was on his shoulders and chest, and the luggage he carried. He staggered into the “Coach and Horses”, more dead than alive, and flung his portmanteau down. “A fire,” he cried, “A room and a fire!” He stamped his foot and shook the snow off himself in the bar, and followed Mrs. Hall into her guest parlour.

Mrs. Hall lit the fire and left him there while she went to prepare his meal. A guest at Iping in the wintertime was an unheard piece of luck, and she was resolved to do her best to please him. She brought the cloth, plates, and glasses and began to lay the table. Although it was warm in the room, she was surprised to see that her visitor still wore his hat and coat. His seemed to be lost in thought. Mrs. Hall noticed that the melted snow dripped upon her carpet. “Can I take your hat and coat, sir,” she said, “and give them a good dry in the kitchen?”

“No,” he said without turning.

She was not sure she had heard him, and was about to repeat her question.

He turned his head and looked at her over his shoulder. “I prefer to keep them on,” he said, and she noticed that he wore big blue spectacles and had bushy whiskers over his coat collar that completely hid his face.

“Very well, sir,” she said. “As you like. In a while the room will be even warmer.”

He made no answer and turned his face away from her again, and Mrs. Hall laid the rest of the table things and whisked out of the room. When she returned he was still standing there, like a man of stone, his back hunched, his collar turned up, hiding his face and ears completely. She put down the eggs and bacon, and called rather than said to him, “Your lunch is served, sir.”

“Thank you,” he said and did not stir until she closed the door.

She noticed that he had taken off his coat and hat and put them on a chair in front of the fire. “Oh,” she thought, “his pair of wet boots can ruin my steel fender!” and said aloud, “I suppose I may dry them now,” she added in a voice that took no denial.

“Leave the hat,” said her visitor, in a muffled voice, and turning she saw he had raised his head and was sitting and looking at her.

For a moment she stood gaping at him, too surprised to speak.

He was holding a white cloth-it was a serviette he had brought with him-over the lower part of his face, so that his mouth and jaws were completely hidden, and that was the reason for his muffled voice.

But it was not that which startled Mrs. Hall. It was the fact that all his forehead above his blue glasses was covered by a white bandage, and that another covered his ears, leaving only his pink nose. It was bright, pink, and shiny just as it had been at first. He wore a dark-brown velvet jacket with a high, black collar turned up about his neck. His thick black hair, between the cross bandages, gave him the strangest appearance imaginable.

He did not remove the serviette, but remained holding it with a brown gloved hand. “Leave the hat,” he said, speaking very distinctly through the white cloth.