William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in the United Kingdom by William Collins in 2017

This William Collins eBook edition published in 2018

Text © Simon Cooper 2017

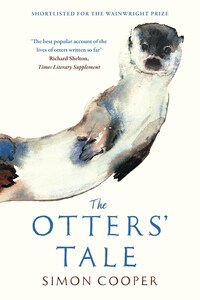

Cover illustration © Curious Otter, 2003 (w/c on paper), Adlington, Mark/Private Collection/Bridgeman Images

The author asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008189747

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008189723

Version: 2018-09-26

‘He summarizes his observations by telling the detailed story of a mother and her young and the male otter with which they occasionally interact. He does so with the charm of a Kenneth Grahame but with the scientific rigour of modern behavioural science. It is the best popular account of the lives of otters written so far.’

Times Literary Supplement

‘Offers something new, and ultimately optimistic.’

New Scientist

‘A wonderful book.’

Daily Mail

‘I loved the gentle flow of this book and the insight into both a pastime and a wonderful corner of the land.’

BBC Countryfile

‘Cooper’s enthusiasm is so infectious’

Daily Mail

‘[Simon Cooper] is a renowned fly-fisher himself and, in this book, he writes as well as he casts […] delightful […] Mr Cooper is in love with chalkstreams and anyone who reads this splendid book will soon hold the same view.’

Country Life

‘We are taken on a delightful journey overflowing with passages that capture our imagination […] It is both uplifting and therapeutic.’

Classic Angling

To Mary and Minnie – muses both.

‘It’ll be all right, my fine fellow,’ said the Otter (to Ratty). ‘I’m coming along with you, and I know every path blindfold; and if there’s a head that needs to be punched, you can confidently rely upon me to punch it.’

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows

Looking back on it, I was something of a fool; the signs had been there for years but it took a fall of January snow finally to reveal what I should have known all along. As night turned into day, the virgin snow around the lake was anything but virgin, the peninsula that divided the lake from the river criss-crossed with seemingly a thousand footprints or more. From river to lake, lake to river and back again, the night-time visitors had clearly been busy, the five clawed paw prints exposing the green grass beneath the broken snow. This animal runway was as churned up as any busy city-centre pavement, but with particularities that told its own unique tale.

The river bank spoke of great effort, the snow ground into mud. Deep impressions in the turf atop the bank were clearly purchase points, the lower bank a mess of icy earth where the creatures had scrabbled to haul themselves from the water. Where the track marks met the lake was a different story. An icy slide, which looked as fun as that of any water park, was worn smooth with regular use, forming the connection between land and water. At the approach a patch of snow, maybe the size of a large door mat, was crushed flat – smooth evidence, to my mind at least, of someone or something lying and rolling in the snow.

In the dull light of pre-dawn one corner of battered snow beneath the tall alder caught my eye. It looked different to the rest and, sure enough, as I approached I could see the mottled snow was flecked with blood, with a bright red patch at its centre. Little bright silvery grey specks, at first unfamiliar, decorated this collage of nature. I stooped down, licked my finger and dabbed at one. A fish scale, shining like translucent mother-of-pearl, glinted back at me. The cogs in my head were gradually clicking into alignment.

A raspy, wheezy cough cut through the silence, and there, at the base of the alder, on the roots that formed a sinewy platform at the lake edge, sat the otter that I would one day know as Kuschta. In truth, she seemed calmer about our accidental meeting than I was. In that fraction of a second in which our eyes locked she assessed me, dismissed me as irrelevant and then turned, in one fluid movement pouring herself into the lake. I, on the other hand, stood rooted to the spot, uncertain what to say or do. I mean really, how daft is that – what could you ever say to an otter? Or do? Well, I did nothing. She, clearly the more evolved one in this particular situation, surfaced a few yards out from the bank before heading for the island that sits in the middle of the lake. On reaching its edge she emitted a single