In 1819, Millworker William Collins from Glasgow, Scotland, set up a company for printing and publishing pamphlets, sermons, hymn books and prayer books. That company was Collins and was to mark the birth of HarperCollins Publishers as we know it today. The long tradition of Collins dictionary publishing can be traced back to the first dictionary William published in 1824, Greek and English Lexicon. Indeed, from 1840 onwards, he began to produce illustrated dictionaries and even obtained a licence to print and publish the Bible.

Soon after, William published the first Collins novel, Ready Reckoner, however it was the time of the Long Depression, where harvests were poor, prices were high, potato crops had failed and violence was erupting in Europe. As a result, many factories across the country were forced to close down and William chose to retire in 1846, partly due to the hardships he was facing.

Aged 30, Williamâs son, William II took over the business. A keen humanitarian with a warm heart and a generous spirit, William II was truly âVictorianâ in his outlook. He introduced new, up-to-date steam presses and published affordable editions of Shakespeareâs works and Pilgrimâs Progress, making them available to the masses for the first time. A new demand for educational books meant that success came with the publication of travel books, scientific books, encyclopaedias and dictionaries. This demand to be educated led to the later publication of atlases and Collins also held the monopoly on scripture writing at the time.

In the 1860s Collins began to expand and diversify and the idea of âbooks for the millionsâ was developed. Affordable editions of classical literature were published and in 1903 Collins introduced 10 titles in their Collins Handy Illustrated Pocket Novels. These proved so popular that a few years later this had increased to an output of 50 volumes, selling nearly half a million in their year of publication. In the same year, The Everymanâs Library was also instituted, with the idea of publishing an affordable library of the most important classical works, biographies, religious and philosophical treatments, plays, poems, travel and adventure. This series eclipsed all competition at the time and the introduction of paperback books in the 1950s helped to open that market and marked a high point in the industry.

HarperCollins is and has always been a champion of the classics and the current Collins Classics series follows in this tradition â publishing classical literature that is affordable and available to all. Beautifully packaged, highly collectible and intended to be reread and enjoyed at every opportunity.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in 1804, with the surname Hathorne. It is widely thought that the reason for the spelling change was that he hailed from the town of Salem, where a number of his relatives had been involved with the infamous witch trials that took place in the closing decade of the 1600s. In fact, his great grandfather, John, had been an executioner. Nathaniel did publish some early material using his original surname however, so it seems more likely that he changed it to save confusion over spelling as it was pronounced in a similar way to âHawthorneâ anyway.

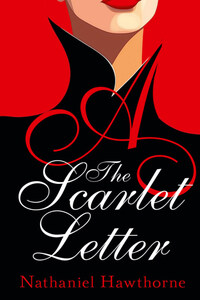

Hawthorne was unsure of his abilities as a writer initially, publishing his first novel Fanshawe anonymously in 1828. In addition, there was no established market for novels so he remained only locally known as a writer until he published The Scarlet Letter in 1850. By then it was possible to mass produce books and this title was one of the first in American literary history. The book also sold well and enabled Hawthorne to become a professional author at a time when one could count them all on one hand.

In a more competitive environment Hawthorne may not have done so well, but as it was he had a ready market waiting to buy his books. Despite their morbidity and intensity they sold well because people had developed a taste for reading fiction. In part this was due to the establishment of stable and polite society in America since the dust had settled from the revolution. It became fashionable to be seen to have the time to read and it gave like-minded people a talking point over dinner and during other social occasions.

Hawthorne was undoubtedly skilled at his craft. He wrote well, had an eye for literary detail and understood that allegory was a useful devise in ensuring that readers got more from his books than just a good story. In this regard he was at odds with Edgar Allan Poe, who was more freeform with his words, indulging in prose that explored the recesses of his imagination without being moralistic or allegorical. One might say that Poe used writing as an art form, while Hawthorne used it as a craft. He took a pragmatic approach by being more mindful of what his readership would wish to read. Poe worked with creative abandon, coming up with ever more challenging visions.