William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins 2014

Copyright © Janice Hadlow 2014

Janice Hadlow asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

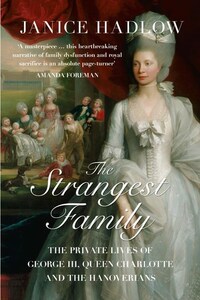

Cover image: Queen Charlotte, 1779 (oil on canvas) by West, Benjamin (1738–1820)/Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015/Bridgeman Images

Source ISBN: 9780007165193

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780008102203

Version: 2015-06-29

WHEN QUEEN CHARLOTTE WAS ASKED by the artist, botanist and diarist Mrs Delany why she had appointed the writer Fanny Burney to the post of assistant dresser in her household, she answered with characteristic clarity: ‘I was led to think of Miss Burney first by her books, then by seeing her, then by hearing how much she was loved by her friends, but chiefly by her friendship for you.’ If questioned about why I wrote this book, I am not sure I could answer with such confident precision. In one sense, it simply crept up on me, emerging from a long love affair with the period and the people who lived in it.

I have always been fascinated by history. I studied it at university, where I was taught by some exceptional and inspiring teachers. As a television producer, I have made many history programmes, covering all aspects of the past – from the ancient world to times within living memory. I have worked with some of the most eminent British historians, witnessing at first-hand their knowledge and passion for a huge variety of subject areas. But it was always the eighteenth century that had first place in my heart. I had immersed myself in the politics of the period at college, but its appeal went far beyond what my reading delivered for me. Like so many others, I was drawn to it partly by the wonderful things made in it: the incomparable architecture that created austerely elegant palaces for the great, and airy, comfortable homes for the ‘middling sort’. I coveted the objects that went into these houses, from the sturdily beautiful furniture to the delicate blue-and-white coffee cups intended to sit proudly on all those much-polished tea tables. I admired the art of the period too, especially the portraiture, whether it was the clear-eyed intensity of Allan Ramsay, the bravura gestures of Joshua Reynolds, or the tender luminosity of Thomas Gainsborough. Those eighteenth-century men and women rich enough to afford it never tired of having themselves painted. If I had been one of them, I would have chosen Thomas Lawrence for my portrait. Who wouldn’t want to see themselves through Lawrence’s humane yet flattering eye, which infused even the most unpromising sitter with a sense of spirit and passion? I would have worn a red velvet dress, as both princesses Caroline and Sophia did when they sat for Lawrence, and hoped for a similarly impressive result: both women gaze directly out from their pictures, proud, commanding and smoulderingly bold. The portraits do not quite capture their true characters, at least as revealed in their letters; but what an image to look upon when your spirits needed a boost.

But much as I responded to the things the period produced, my real desire was to understand the people who lived in it. It was the men and women of what is often called the long eighteenth century – which runs from the accession of George I in 1714 to the death of George IV in 1830 – who really captivated me. Caught between the religious intensity of the seventeenth century and the earnest high-mindedness of the Victorians, this was a society in which I felt very much at home. I enjoyed its bustle and energy, and liked being in the company of its garrulous, argumentative and emotional inhabitants. The contradictions of their world intrigued me. On the one hand, they loved order, politeness, restraint. On the other, they were loud, forthright and often violent. The sedate drawing rooms of the rich looked out onto streets where passions could and did run very high. The poor, in both town and country, had a tough time of it, although they too seem to have shared something of the assertive confidence of the wealthy. For most of the middling sort, however, and especially for the rich, there was good reason to be bullish. This was a period in which there was money to be made, and a new kind of life to be lived. It is the experiences of these people – those who built the houses, big and small, laid out the gardens, commissioned the pictures, bought the furniture – that I have come to know best.