![]()

Some places announce themselves by a distinctive smell in the air, long before the town or city itself is reached: the hoppy aroma of brewing from Burton, the lingering smell of the old fish docks in Grimsby, the sulphurous fire and brimstone of the forges that used to announce Sheffield, or the acrid stink of the Billingham chemical works. York greets its visitors with an altogether sweeter and more enticing smell: the rich, mouth-watering aroma of chocolate drifting on the breeze from the Rowntree’s factory just to the north of the city centre. The company, by some distance the city’s largest employer, was taken over by Nestlé in 1988, but to the citizens of York it will always be known as ‘Rowntree’s’.

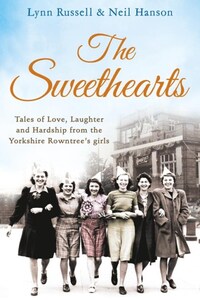

This is the story of some of the Rowntree’s Sweethearts – the women workers from the company’s Golden Age, which spanned the half-century from the 1930s to the 1980s. That era began at a time when a woman’s right to vote had at last been established, but her right to choose her career path, manage her own money, live her own life and follow her own destiny was far from certain. In the 1930s and the decades that followed, many of the women employed at Rowntree’s found a degree of financial independence, self-confidence and self-reliance through the money they earned at the factory, the skills they acquired and, of no lesser importance, the bonds they formed with other women workers. For some unhappy women, whose lives were blighted by poverty, illness, bad housing and even bad husbands, their working days at the factory also offered a much-needed refuge and respite from their domestic turmoil – a place where they could be happy, respected and valued by their workmates.

The women to whom we spoke in the course of our research were all unstintingly generous with their time and their memories, but it’s a sobering thought that, had this book not been published, their extraordinary, moving and inspirational stories might well have gone untold and unrecorded. They loved their time at Rowntree’s and still regard the factory and the company with great affection. It was, they said, ‘a great place to work and a real community’. They had the Yorkshire virtues: warmth, compassion, honesty, truthfulness, thrift and the capacity for hard graft. They did a fair day’s work in return for a fair day’s pay, shared laughter and tears, hardship and good times, and in the process they helped to make Rowntree’s – and York – what it is today.

Lynn Russell and Neil Hanson, April 2013

Rowntree’s confectioners hand-decorating Easter eggs, c.1930s. ©Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Hand-piping the decorations on the tops of chocolates (possibly Dairy Box), late 1940s. ©Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Ladies packing Smarties into ‘cinema cartons’, early 1950s. ©Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

A new recruit undergoes psychological assessment in the Rowntree’s psychology department, c.1950s. ©Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Married women work in the seasonal section, wrapping Easter eggs in foil and tying them up with ribbons, 1954. ©Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Ladies of the Cake department pack six penny bars of Milk Motoring Chocolate into ‘outers’ ready to be sent out to retailers. ©Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Cyclists on Haxby Road, a quarter of a mile from the Rowntree’s factory, c.1920s. ©Stephen Barrett

On a warm Monday morning in July 1932, Madge Fisher stood fidgeting in the hallway of her terraced house while her mother, Margaret, pinned up her hair and then inspected her from top to toe. ‘Hands,’ her mother said, and Madge presented them meekly for inspection, glad that she’d remembered to wash them at the kitchen sink. She was a petite blonde girl with a quick wit and a ready smile, but her mum was a force of nature, a big, powerful woman, warm and loving, but leaving no one in any doubt that she was the boss of her own household. At seventeen stone, she dwarfed her diminutive daughter, and one look from her was enough to let Madge know when she’d done something wrong.

The front door, opening straight onto Rose Street, stood ajar, and the sun streaming through it cast a long rectangle of light onto the threadbare strip of carpet in the hall and the scuffed toes of the hand-me-down shoes Madge had inherited from one of her sisters. She fidgeted even more as her mum straightened the collar of her dress and repinned her hair for the third time. ‘I’m going to be late if I don’t go now, Mam,’ Madge said, so with a last critical glance at her daughter, Margaret hugged her and then stood on the doorstep to wave her off.

There was the sound of horse’s hooves and a brief, warm smell of stables as a horse and cart plodded slowly past, the rag and bone man’s cry of ‘Rag and Bo-o-o-o-ne’ echoing from the walls. He sat with the reins held loosely in his lap, the open cart behind him already littered with a few bundles of rags and a heap of thick beef bones left over from Sunday joints. Nothing was wasted in those days. Madge’s mum collected used brown-paper bags, carefully smoothing and folding them and putting them in the kitchen drawer for later use. They shared the drawer with bits of string, coiled and tied like small bowties, and rubber bands and paperclips that were stored in neatly labelled old tobacco tins. Food was never thrown away but used and reused, so that Sunday’s roast meat would be served cold on Monday (washday), reheated in a stew on Tuesday, then minced and cooked as a shepherd’s pie on Wednesday, and the last of it served up as rissoles on Thursday. Friday, of course, was always a fish day.