“We are still – though in a somewhat free handwriting and a way that is upsetting enough to the bourgeois – painting the things of “reality”: people, trees, country fairs, railroads, landscapes. In that respect we are still obeying a convention. The bourgeois calls those things “real” which are seen and described pretty much the same way by everybody, or at least by many people.”

Hermann Hesse, Klingsor’s Last Summer

![]()

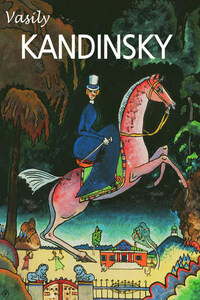

Exotic Birds, Tretyakow Gallery, Moscow.

Not long ago it seemed that this century had not only begun with Kandinsky, but ended with him as well.[1] But no matter how often his name is cited by the zealots of new and fashionable interpretations, the artist has passed into history and belongs to the past and to the future to a greater degree, perhaps, than to the present. So much has been written and said about Kandinsky. His works, including his theoretical ones, are so well-known that this abundance of knowledge and commonplace opinions often hinders our seeing the artist in his individuality, in his real – not mythologized – significance. With a fresh gaze. From the threshold of the third millennium.

Weary of arch postmodernist games, the experienced and serious viewer today seeks in Kandinsky that which no one had seen in him earlier – and had not attempted to see: a buttress in an unstable world of artistic phantoms and fashionable shams. What just less than a hundred years ago was born as a bold revelation has now passed over into the category of eternal values. Among the titans of modernist art, Kandinsky was a patriarch. Matisse was born in 1869; Proust, in 1871; Malevich, in 1878; Klee, in 1879; Picasso, in 1881; Kafka, in 1883; Chagall, in 1887. Kandinsky himself was born in 1866, a year that also witnessed the birth of Romain Rolland and the publication of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Anna Karenina had yet to be written and no one had yet pronounced the term “Impressionism.” Kandinsky, in a word, was born in “the very depths” of the nineteenth century. Kandinsky was twenty when the last exhibition of the Impressionists opened; he was thirty-four when Ambroise Vollard held the young Picasso’s first one-man show in his gallery. At the turn of the century Kandinsky was only just beginning to become a professional, his name was still unknown – and he did not yet know himself.

Gouspiar, Tretyakow Gallery, Moscow.

Prayer.

The Port of Odessa, late 1890s.

Oil on canvas, 65 × 45 cm, Tretyakow Gallery, Moscow.

Kandinsky’s intellectualism and that of his art have constantly been noted by scholars and essayists. This situation is not typical: the young paladins of the avant-garde attracted their adepts not so much with knowledge and logic as with the radicalism and the spiritedness of their opinions; and, more often, with a meaningful incomprehensibility interspersed with brilliant revelations. The destiny of a master who linked his art with Russia, Germany and France; his work as a teacher in the celebrated Bauhaus; his prose, verse and theoretical writings; his unbending and determined path towards individuality – all of these things have made Kandinsky more than just another of the great artists of the twentieth century. In the culture of our age he has occupied a quite exceptional place: the place of an artist alien to vanity and with a desire to shock the viewer; the place of a master inclined to constant and concentrated meditation, to unswerving movement towards a synthesis of the arts, to the quest for more perfect, ascetic and strict formal systems. Moreover, Kandinsky’s art does not reflect (or, if one may say so, is not burdened by) the fate of other Russian avant-garde masters. He left Russia well before the semi-official Soviet esthetic turned its back on modernist art. He himself chose where he would live and how he would work. He was forced neither to struggle with fate nor to enter into conspiracy with it. His “struggles” took place “with himself” (Boris Pasternak). The persecutions to which “leftist” artists in Russia were subjected left him untouched and did not complicate his life. Neither, however, was he was awarded a crown of thorns or the glory of a martyr, like the lot of those famous avant-garde artists who remained in Russia. His reputation is in no way obliged to fate – only to art itself. The culture of the past was for him precious and intelligible: he was not concerned with the smashing of idols. Creating the new occupied him entirely. He aspired neither to iconoclasm nor to scandalous behavior. It could hardly be said that his work lacked daring, but this was a daring saturated with thought, a polite daring argued with art of the highest quality.

Landscape Near Achtyrka, Tretyakow Gallery, Moscow.

Achtyrka. Autumn, sketch, 1901.

Oil on canvasboard, 23.7 × 32.7 cm, Municipal Gallery of Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Munich. Schwabing