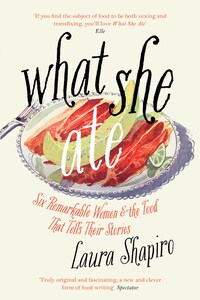

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © Laura Shapiro 2017

Cover illustration © Getty Images

Laura Shapiro asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

The author is grateful for permission to quote from letters and other materials held by the following: The Wordsworth Trust, Dove Cottage, Grasmere; Nancy Roosevelt Ireland and the literary estate of Eleanor Roosevelt; Justice Michael A. Musmanno Collection, University Archives and Special Collections, Gumberg Library, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA; the Estate of Barbara Pym; the papers of Barbara Mary Crampton Pym (1913–80), Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; Julia Child Materials © 2016; Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts

Photo credits: Dorothy Wordsworth: Artist unknown. Photo by Hugh Thomas. This image has been reproduced by kind permission of the Wordsworth family, direct descendants of William Wordsworth and owners of Rydal Mount. Rosa Lewis: Granger, NYC. All rights reserved. Eleanor Roosevelt: Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library. Eva Braun: Photo by Heinrich Hoffmann. Bavarian State Library Munich/Hoffmann collection. Barbara Pym: Photo by Mark Gerson. Helen Gurley Brown: Photo by John Bottega. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Collection, Library of Congress.

Portions of this book have appeared, in different forms, in The New Yorker and Food and Communication (Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2015) and on the website of the Barbara Pym Society.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008281106

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008281083

Version: 2018-06-08

For Jack

How many things by season seasoned are …

—William Shakespeare,

The Merchant of Venice

Many a non-Chinese has come away from a meal cursing the “inscrutable” Chinese for saying nothing but bland, polite phrases, when the meal itself was the message, one perfectly clear to a Chinese.

—E. N. Anderson and Marja L. Anderson, in Food in Chinese Culture, edited by K. C. Chang

Tell me what you eat,” wrote the philosopher-gourmand Brillat-Savarin, “and I shall tell you what you are.” It’s one of the most famous aphorisms in the literature of food, and I thought about it many times as I was probing the lives of the six women in this book. Food was my entry point into their worlds, so naturally I wanted to know what they ate, but I wanted to know everything else, too. Tell me what you eat, I longed to say to each woman, and then tell me whether you like to eat alone, and if you really taste the flavors of food or ignore them, or forget all about them a moment later. Tell me what hunger feels like to you, and if you’ve ever experienced it without knowing when you’re going to eat next. Tell me where you buy food, and how you choose it, and whether you spend too much. Tell me what you ate when you were a child, and whether the memory cheers you up or not. Tell me if you cook, and who taught you, and why you don’t cook more often, or less often, or better. Please, keep talking. Show me a recipe you prepared once and will never make again. Tell me about the people you cook for, and the people you eat with, and what you think about them. And what you feel about them. And if you wish somebody else were there instead. Keep talking, and pretty soon, unlike Brillat-Savarin, I won’t have to tell you what you are. You’ll be telling me.

One of the reasons I began writing about women and food more than thirty years ago was that I was full of questions like these, and I couldn’t find enough to read to satisfy my, well, hunger. Plainly women had been feeding humanity for a very long time, but for some reason only the advertising industry seemed to care. History, biography, even the relatively new field of women’s studies weren’t producing what should have been floods of books on female life at the stove or the table. I couldn’t figure it out. Surely women spent more time in the kitchen than they did in the bedroom, yet everybody was studying women and sex, and nobody was studying women and cooking except the companies selling cake mix. Maybe because I was a journalist, not an academic, it struck me as obvious that everyday meals constitute a guide to human character and a prime player in history; but I began to see that food was a tough sell in the scholarly world. The great minds were staunchly committed to the same great topics they had been mulling for centuries, invariably politics, economics, justice, and power. Today we know that all these issues and more can be brought to bear on the making of dinner—those stacks of books that were once missing are piled high by now—but back then the great minds, not to mention most of their graduate students, were reluctant to descend to the frivolous realm of the kitchen. After all, academic reputations were at stake. Home cooking was associated with women, which was bad enough, and housework,