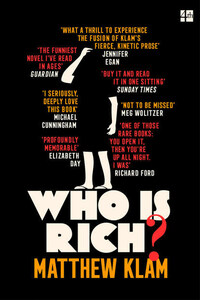

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published in the United States by Random House in 2017

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © 2017 by Matthew Klam

Drawings copyright © 2017 by John S. Cuneo

Cover design by Jack Smyth

“Sea-Level Elegy” was first published in Stag’s Leap (Jonathan Cape 4th October, 2012). Reprinted by permission of Jonathan Cape and Aragi Inc.

Matthew Klam asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008282516

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008282523

Version: 2018-03-23

Once, each summer, I howl,

and draw myself back, out of there, where

desire and joy, where ignorance, where

touch and the ideal, where unwilled yet willful

blindness – once a year, I have mercy,

I let myself go down where I have lived, and then,

hand over hand, I pull myself back up.

“Sea-Level Elegy”, Sharon Olds

Fog blew in Saturday morning. I sat under a big white tent and drank some coffee while my chair sank into the lawn. I talked to a kid with a heavy beard in a mangled straw hat who last year for some reason we started calling Swaggamuffin.

A girl wearing a name tag passed out rosters to faculty. A guy walking behind her handed me an info packet. I sat there eating toast, looking at my notes. Other people were out there too, chatting and smoking. I said hello to a dozen familiar faces from over the years and drank several more cups. The fog burned off. A lawnmower buzzed. The sky was a flawless aquamarine blue.

I’d written a three-part lecture, on drawing techniques, brainstorming, and plotting, and also found some handouts with exercises from last year or the year before that. We supplied them with pencils, erasers, pens, nibs, brushes, and paper—100-pound acid-free Bristol board for comic applications—and a little plastic thing called the Ames Lettering Guide, which I still had no idea how to use.

We were gathered on the campus of a college you’ve never heard of, at the end of a sandy, hook-shaped peninsula, bound by the Atlantic and scenic as hell. It was my fifth straight summer running a workshop at an annual summer arts conference, and once again my class was full. The conference had begun fifteen years before as a one-day poetry festival and had grown every year in size and popularity, although the college itself had not fared as well. Over time, pieces of it had been boarded up to save money until the entire school was abandoned, then reopened in a limited capacity as a satellite of the nearest state U. The college had kept its name, which was the name of the town, which had been named after the people who’d been here since the beginning of time, who’d made peace with the English settlers, teaching them to fish and hunt, helping them slaughter neighboring tribes, before they too were wiped out by disease or dragged off and sold into slavery.

Nada Klein, with her long French braid and dark wolfish eyes, walked through the tent with her shawl dragging on the ground. She beat cancer every year, and showed up late to her own slide talks, and was widely mocked and imitated. Larry Burris was back, too. He skipped his meds one year and wore a jester’s cap to class and lit his own notes on fire, and had to spend the night in a hospital. He stood beside me now, beneath the tent flap, patiently signing a copy of his book, and handed it back to a woman who hugged him. On the faculty were many friends I’d come to know over the years as intellects, historians, wordsmiths, talented performers, storytellers with big fake teeth, addicts, drunkards, perverts, world-famous womanizers, sufferers of gout, maniacs, liars—embittered, delusional, accomplished, scared of spiders, unable to swim, loveless, and cruel. I noticed Barney Angerman, who’d won the Pulitzer for drama the year I was born, and Tabitha Portenlee, who’d written an acclaimed incest memoir; she was helping Barney through the breakfast line as he gripped her arm. This past winter the conference director had asked me to name another cartoonist I could vouch for to teach a second comics workshop, but I didn’t answer him. I worried, because of the way my career had gone, that I’d be hiring my replacement.