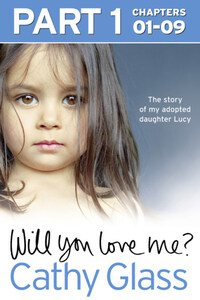

Will You Love Me?: The story of my adopted daughter Lucy: Part 1 of 3

Will You Love Me can either be read as a full-length eBook or in 3 serialised eBook-only parts.This is PART 1 of 3 (Chapters 1-9 of 27).You can read Part 1 two weeks ahead of release of the full-length eBook and paperback.The eleventh memoir and latest title from the internationally bestselling author and foster carer Cathy Glass. This book tells the true story of Cathy’s adopted daughter Lucy.Lucy was born to a single mother who had been abused and neglected for most of her own childhood. Right from the beginning Lucy’s mother couldn’t cope, but it wasn’t until Lucy reached eight years old that she was finally taken into permanent foster care.By the time Lucy is brought to live with Cathy she is eleven years old and severely distressed after being moved from one foster home to another. Withdrawn, refusing to eat and three years behind in her schooling, it is thought that the damage Lucy has suffered is irreversible.But Cathy and her two children bond with Lucy quickly, and break through to Lucy in a way no-one else has been able to, finally showing her the loving home she never believed existed. Cathy and Lucy believe they were always destined to be mother and daughter – it just took them a little while to find each other.