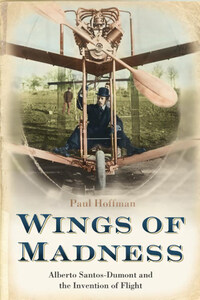

PAUL HOFFMAN

WINGS OF MADNESS

ALBERTO SANTOS-DUMONT

AND THE INVENTION

OF FLIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Paul Hoffman 2003

Paul Hoffman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

SOURCE ISBN: 9781841153681

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007441082

Version: 2016-10-11

For Ann and Alexander and Matt

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue Dinner on the Ceiling Champs-Elysées, 1903

1 Arrival Minas Gerais, 1873

2 “A Most Dangerous Place for a Boy” Paris, 1891

3 First Flight Vaugirard, 1897

4 Dying for Science Paris, 1899

5 The Turkey Buzzard’s Secret

6 An Afternoon in the Rothschilds’ Chestnut Tree Paris, 1901

7 “It Is the Poor Who Will Suffer!” The Eiffel Tower, 1901

8 “Making Armies a Jest”

9 An Unwelcome Dip in the Mediterranean Bay of Monaco, 1902

10 “Airship Is Useless, Says Lord Kelvin” London and New York, 1902

11 The World’s First Aerial Car Paris, 1903

12 A Scurrilous Stabbing and a Russian Bribe St. Louis, 1904

13 “Aeroplane Raised by Small Motor, M. Santos-Dumont Performs a Feat Never Before Attained in Europe” Paris, 1906

14 “A War of Engineers and Chemists”

15 “Cavalry of the Clouds”

16 Departure Guarujá, 1932

Postmortem In Search of a Heart Campo dos Afonsos, 2000

What Santos-Dumont Wrote

What Santos-Dumont Read

What Santos-Dumont Made

Notes

Index

Origins and Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

IN DECEMBER 1903, an eleven-year resident of Paris, the Brazilian aeronautical pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont, held a small holiday party in his high-ceilinged apartment on the Champs-Elysées. Louis Cartier, the jeweler, was there, as was Princess Isabel, the daughter of the last emperor of Brazil. The other attendees can only be surmised because there was no printed guest list, but his regular dining partners and confidants included George Goursat, the flamboyant writer and cartoonist who drew caricatures of the rich and famous on the walls of the city’s fanciest restaurants; Gustave Eiffel, the architect of the eponymous tower; Antônio Prado Jr., the son of the Brazilian ambassador; two or three Rothschilds, who first met their thirty-year-old host when his experimental airship crashed in their gardens; Empress Eugénie, Napoleon III’s reclusive widow; and assorted kings, queens, dukes, and duchesses too numerous to name.

When Santos-Dumont’s butler ushered the guests into the dining room, they were amused to find that they had to climb a stepladder so that they could sit on tall chairs positioned around a table higher than they were. But they were not surprised. Since the late 1890s Santos-Dumont had been giving “aerial dinner parties.” The first ones were held at an ordinary table and chairs suspended by wire from the ceiling. This worked when the hundred-pound Santos-Dumont dined alone, but when a group assembled, the ceiling eventually gave way under the collective weight. Santos-Dumont was a skilled craftsman, who had learned woodworking from the men on his father’s coffee plantation, so he built the long-legged tables and chairs that had become a fixture of his apartment ever since. At the first elevated soirees, his guests, between sips of milky green absinthe, invariably asked what the point of the high table was. And their shy host, who preferred to let others do the talking, would run his bejeweled fingers through his jet-black hair, which was parted in the middle, in a style seen almost exclusively on women, and impishly explain that they were dining aloft so that they could imagine what life was like in a flying machine. The guests laughed. Flying machines did not exist in the 1890s, and received scientific wisdom said that they never would. Santos-Dumont ignored the snickering and insisted that they would soon be commonplace.

Hot-air balloons, to be sure, were a familiar sight in the skies of fin de siècle Paris, but they were not flying machines. With no source of power, these large floating orbs—they were described as spherical although they actually had the shape of an inverted pear—were entirely at the mercy of the wind. By the turn of the century, Santos-Dumont changed that. He strapped an automobile engine and propeller to the balloon and, to make it aerodynamically efficient, switched its shape to that of a sleek cigar. On October 19, 1901, thousands of people turned out to watch him circle the Eiffel Tower in his innovative airship. The crowds on the bridges over the Seine were so thick that people were shoved into the river when they scaled the parapets to get a better view. The scientists who observed the flight from Gustave Eiffel’s apartment at the top of the tower were sure he would not make it. They feared that an unpredictable wind would impale him on the spire. Others were convinced that the balloon would explode. When Santos-Dumont proved them wrong, Jules Verne and H. G. Wells sent congratulatory telegrams.