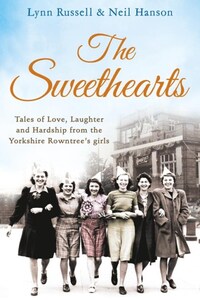

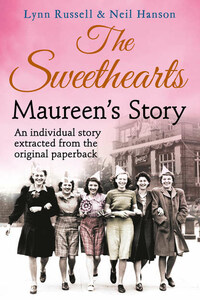

Maureen’s story

This is Maureen’s story, one of five stories extracted from THE SWEETHEARTS.Whether in wartime or peace, tales of love, laughter and hardship from the girls in the Rowntrees factory in Yorkshire.“Maureen started work at Rowntree’s on her fifteenth birthday in April 1959, and remembers being the only one in the entire workforce who was wearing ankle socks. But she soon settled in and on Saturday afternoons Maureen and the rest of the girls would go into town – 'I really liked the fashions then and used to love getting dressed up in those days. We wore stockings and suspenders, stilettos, and we always wore gloves, usually white ones, and shoes and handbag to match. We all wore skirts under our overalls and hooped petticoats. My digs were just over the bridge from Rowntree’s and the boys used to love watching me run down the bridge in the morning! I was never late for work, but I usually cut it pretty fine and often had to run the last couple of hundred yards. The hoops would ride up while I was running so there’d be a lot of wolf whistles from the boys…’”From the 1930s through to the 1980s, as Britain endured war, depression, hardship and strikes, the women at the Rowntree’s factory in York kept the chocolates coming. This is the true story of The Sweethearts, the women who roasted the cocoa beans, piped the icing and packed the boxes that became gifts for lovers, snacks for workers and treats for children across the country. More often than not, their working days provided welcome relief from bad husbands and bad housing, a community where they could find new confidence, friendship and when the supervisor wasn’t looking, the occasional chocolate.