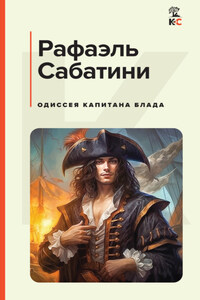

Peter Blood was a bachelor of medicine and lived in Water Lane in the town of Bridgewater.

As he smoked a pipe and watered the flowers on his windowsill, two pairs of eyes watched him from a window opposite. But Mr. Blood did not pay attention to them. He was thinking about the flowers and the people in the street. They were going to Castle Field for the second time that day. Earlier in the afternoon Ferguson, the Duke’s chaplain, had given a speech there.

Most of the people were men with green branches in their hats and pikes in their hands. They were traders of all kinds. Many strong men from Bridgewater and Taunton[1] went to serve in the Duke’s army. People said that the girls of Taunton had even taken their petticoats and made the banners for King Monmouth’s army[2]. People called those men who did not join the army cowards or papists.

Peter Blood was not a coward and he was a papist only when he wanted to. And he had been a soldier. However, he watered his flowers and smoked his pipe on that warm July evening. He looked at the people in Water Lane and said a line of Horace[3]:

“Quo, quo, scelesti, ruitis?”[4]

And now perhaps you understand why he was quiet and did not join the people in Water Lane. He thought that they were fools with their banners of freedom. That Latin line tells you that. To him they were fools running towards their deaths.

You see, he knew too much about this Duke of Monmouth and his mother. He had read the proclamation posted at the Cross at Bridgewater – and he knew that it had been posted also at Taunton and in other towns. It said that “the high-born Prince James, Duke of Monmouth, son and heir to King Charles the Second was now King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland.” He had laughed at it and he had laughed at the next proclamation. It said that James, Duke of York, had poisoned the King and did not have the right to the Crown.

He did not know which was the greater lie.

Mr. Blood had spent a third of his life in the Netherlands. James Scott – who now called himself James the Second – was born there some six-and-thirty years ago, and Mr. Blood knew his story. James Scott was not an heir to the King of England and it was quite possible that he was not even his son. He would only bring ruin to England. He had ordered the people in Water Lane to go to war!

“Quo, quo, scelesti, ruitis?”

He laughed. Mr. Blood was very self-sufficient and unsympathetic. His life had taught him so. He knew – as all Bridgewater knew and had known now for some hours – that Monmouth wanted to fight the Royalist army under Feversham that same night. Mr. Blood thought that Lord Feversham would know it too.

Peter Blood finished smoking, and went to close his window. He looked across the street and met at last the angry look of the eyes that watched him. They were the eyes of the young Misses Pitt. They admired the handsome Monmouth more than anyone in Bridgewater.

Mr. Blood smiled and greeted them. He was friends with these ladies; one of them had been his patient. But they did not answer his greeting. They looked at him in a cold and angry way. His smile grew a little wider, a little less pleasant. He understood why they did it. The Misses Pitt did not like that he, as a young man who had been at war, stayed at home, smoked his pipe, and watered his flowers. They wanted him to go to Castle Field and fight to put Monmouth on the throne. So did women of all ages in Bridgewater.

Mr. Blood might have argued with these ladies. He had travelled a lot and now he just wanted to be a doctor. It was what he had always wanted to do and what he had studied. Peter Blood was a man of medicine and not of war; he wanted to help people, not to kill them. But Misses Pitt and other women in Bridgewater would have answered him, he knew, that he should not stay at home now. Misses Pitt would have said that their nephew Jeremy went to fight for freedom and that Jeremy was a sailor. But Mr. Blood did not want to argue. As I have said, he was a self-suficf ient man.

He closed the window, and turned to the room. Mrs. Barlow was setting the table for supper. He told her what he was thinking about.

“Those two vinegary virgins over the way are very unfriendly.”

Peter Blood had a pleasant voice and an Irish accent. In all his travels he had never lost it. It was a voice that could talk nicely or make orders. The man’s whole nature was in his voice. He was tall and thin, his skin was dark, and his eyes blue under the black eyebrows. By the look of his eyes you could see that he thought high of himself. He was always dressed in black, because he was a doctor, but also because he used to travel a lot and loved elegant clothes.

Now that you know Mr. Blood a little bit better, you might ask yourself how long such a man would stay in the quiet Bridgewater and work as a doctor. He came to Bridgewater some six months ago and he might have stayed there in peace and settled down completely to the life of a doctor. It is possible, but not probable. However, his life would soon change completely.