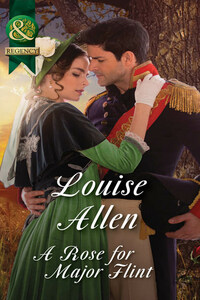

Chapter One

July 1816, Norfolk

The man in the mask ran one hand down the neck of the ugly gray hunter. âPatience, Tolly. One more to go and then itâs oats for you and two dozen of the finest old brandy for me.â

The horse snorted, his ear flicking back to listen to his riderâs voice as Jonathan slouched into the familiar comfort of the saddle, eyes narrowed against the late-evening light. It was past eight now and no traffic had passed along the lane for half an hour. Up to then business had been brisk and last nightâs wager seemed easily won. He dug a hand in his pocket and drew out the tokens he had claimed, proofs of a kiss from each of the first five women who passed down the lane on their way back from market in St. Margaretâs to the villages of Saintâs Mead and Saintâs Ford.

There was a downy feather from the empty egg bucket of the country lass who had giggled and returned his kiss with relish; a tiny corn dolly from the elderly dame driving her donkey cart back, her baskets of straw plait almost empty, a twinkle in her eyes as she pinched his chin; a paper of pins from the thin-faced spinster who had blushed like a peony when he had respectfully saluted her papery cheek; and a promissory note for one ginger kitten (guaranteed of good mousing stock) from the farmerâs wife who had roared with laughter and tipped up her round red face with cheerful anticipation.

Jonathan pinned the corn dolly to his lapel, stuck the feather in his hat brim and wondered which of his housekeepers would most appreciate a kitten. His pleasure in the eveningâs sport began to wane. He had another hour before he was due to join his friends at The Golden Lion for supper to present evidence of his success and the chances of the required fifth female happening along seemed increasingly poor.

Tolly lifted his head and pricked his ears. âHoofbeats,â Jonathan concurred. âOne horseâlikely to be a man.â He nudged the gray through a gap in the thick hedgerow, drew the empty pistol, laid it along his thigh and waited.

âDespicable, hypocritical swine,â Sarah Tatton repeated, reining in her mare to a walk and dashing the tears out of her eyes with an impatient hand. Careering around the countryside sidesaddle in evening dress was far from comfortable now that her initial fury had simmered down, to be replaced by something approaching panic.

How could she have been so meek, so trustingly innocent? Eighteen months sitting in the country, perfecting her wifely skills in domestic management, needlework and entertaining, while Papa boasted to all and sundry of the excellent match he had made for his daughterâand what had she to show for it? Her linen cupboard was immaculate, her stillroom a marvel, she could play a sonata and hold her own in the most trying dinner-party conversation and, finally, her betrothed had deigned to turn up to discuss the wedding.

Sir Jeremy Peters might be only moderately good-looking and not possess a sparkling wit, but he was, as everyone had told her during the course of her second Season, a catch for the daughter of a country baronet with moderate looks and a moderate dowry to match. Wealthy, well-connectedâshe could not hope to do better to oblige her papa.

âRespectable?â Sarah swore under her breath. Half an hour in his company, during which he had congratulated her on her modest gown and presented her with a hideous string of lumpy freshwater pearls had made her heart sink; she had not remembered him as being so dull. But when she had gone upstairs to change for dinner Mary, her maid, had broken down in floods of tears as she fastened her gown.

âIâve got to tell you, Miss Sarah. I cannot let you marry him, not even if it means my place,â she had wailed. What Sarah had heard took her breath away and left her sick and shaken. Sir Jeremy had assaulted Mary at the house party where he had proposed to Sarah and threatened that he would tell Sir Hugh Tatton that she had offered herself for money if she said one word of it.