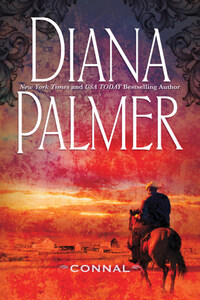

Maureen Harris was already an hour late for work. One thing after another had conspired to ruin her morning. The washing machine in her small duplex in the suburbs had flooded, her last pair of hose had run just as she put them on, then she’d misplaced her car keys. She ran into the offices of MacFaber Corporation bare-legged with her long black hair threatening to come down from its braided bun on top of her head, her full skirt stained with coffee that she’d tried to substitute for breakfast in a drive-through place on the way.

A tall, burly man was just coming around the corner as she turned it, coffee cup still in hand. She collided with him with a loud thud, fell backward, and the coffee cup seemed to upend in slow motion, pouring its contents all over the carpet, splashing him, and splattering her skirt even more.

She sat up in the ruins of it all, quickly retrieving her wire-rimmed, trendy new glasses from the floor and sticking them on her nose so that she could see. She stared up blankly at the taciturn, very somber man in gray coveralls, her green eyes resigned. “I didn’t pay my phone bill on time,” she said, apropos of nothing. “The telephone company has ways of getting even, you know. They flood your washing machine, put runs in all your stockings and cause you to spill coffee and trample strange men.”

He cocked a heavy eyebrow. He wasn’t handsome at all. He looked more like a wrestler than a mechanic, but that was definitely a mechanic’s coverall he was wearing. His dark eyes ran over her like hands, narrowing, curious, and a faint smile touched the mouth that seemed carved out of stone. It was a nice, man’s mouth—wide and sexy and deliberate. He looked Roman, in fact, right down to the imposing nose and brooding brow. Maureen knew all about brooding brows; she had once taken an art class and spent long hours dreaming of imposing Romans. That had been years ago, of course, before she discovered reality and settled down to being a junior secretary in the MacFaber Corporation.

Since he didn’t speak or offer a hand, she scrambled to her feet, staring miserably around at the coffee splatted all over the champagne-colored carpet. She pushed back her hair. “I’m very sorry that I ran into you. I didn’t mean to. I really don’t know what to do.” She sighed. “Maybe I ought to quit before I’m asked to.”

“How old are you?” the man in the mechanic’s outfit asked. He had a gravelly voice—very deep, like rich velvet.

“I’m twenty-four,” she said, faintly surprised by the question. Did he think she was too young for the job? “But usually I’m very competent.”

“How long have you been here?” he asked, eyeing her suspiciously.

“Just since the month before last,” she confessed. “Well, I’ve been here in this new building since it opened, that is. But I’ve worked for the corporation for six months.” Since just before my parents died, she could have said, but she didn’t. “I was chosen out of the typing pool to take one of the old secretaries’ places. I’m very fast. I mean, my typing is very fast. Oh, dear. Do you suppose I could rush out for some sand and toss it over this stain in the carpet before someone sees?”

“Call the janitorial staff. That’s what they’re paid to do,” he said. “You’d better get busy. MacFaber doesn’t like idle employees. Or so I’m told,” he added in a cold, steady tone.

She sighed. “I don’t think he likes anybody. He never sticks his nose in here, anyway, so it’s a good thing the company can run itself. He never comes here, they say.”

Both bushy eyebrows went up. “Do tell? I thought he worked in this building?”

“So did we,” she agreed. “But then, we all came up from the old engineering building when this new building was completed three months ago and they added so much new staff. The secretaries, I mean. Even Mr. MacFaber’s secretary, Charlene, is new, so none of the secretarial staff has ever laid eyes on him. And Charlene gets her work through the vice president in charge of production, kind of secondhand from the big boss,” she added, leaning close. “We suspect that he’s disguised as the big chair in the boardroom.”