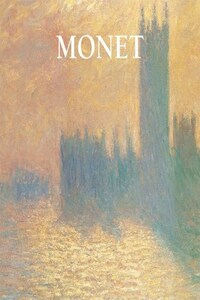

Impression, Sunrise. (Soleil levant, Musée Marmottan, Paris) was the name of one of the paintings that Claude Monet displayed in 1874 at the first exhibition of the “Society of anonymous painters, sculptors, engravers, etc.” It is a landscape painted early in the morning.

In the Garden, under the Trees Le Moulin de la Galette

Auguste Renoir

Oil on canvas, 81 × 65 cm

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The grey mist turns the shapes of the ships’ sails into ghosts; the black silhouettes of the boats slide over water, and the sun is coming up as a flat orange disc, which traces its orange path on the surface of the water. It was not exactly a painting, but rather a quick sketch, a free draft in oil.

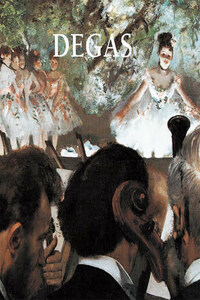

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas, 1858–67

Oil on canvas, 200 × 250 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The painting’s name, The View of Le Havre, did not really correspond to the painting – one cannot see Le Havre in it at all. “Call it Impression”, Monet told Renoir, who was compiling the catalogue, and this was the beginning of the history of Impressionism.

Young Spartan Girls Challenging the Boys

Edgar Degas, ca. 1860

Pencil on paper, 22.9 × 36 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

On 25 April, 1874 the critic Louis Leroy published a satirical piece in the Charivari newspaper, which narrated his visit to the exhibition. The surface of the work by Camille Pissarro depicting a ploughed field appeared to him to be scraped dried paint from the palette thrown onto a dirty canvas.

Self-Portrait

Edgar Degas, ca. 1863

Oil on canvas, 92.1 × 66.5 cm

Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon

He was terrified by Claude Monet’s Paris scene entitled Boulevard des Capucines. He stopped in front of the landscape from Le Havre painted by Monet and asked what the painting meant. Impression, Sunrise. “Impression!” the journalist snorted.

Bunch of Peonies

Edouard Manet, 1864

Oil on canvas, 93 × 70 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

“Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished!” (Charivari, 25 April, 1874). Leroy named his article, ‘The Exhibition of the Impressionists’. With a truly French linguistic agility, he coined a new word from the title of the painting. Within a year, the name “Impressionism” was an accepted term – the art itself was not.

Garden of the Princess

Claude Monet, 1867

Oil on canvas, 91 × 62 cm

Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio

The term turned out to be so accurate that it was destined to stay forever in the history of art. The group of the future Impressionists had been formed in the early 1860s; and the term “Impressionism” came to mean a trend not only in French art, but in fact, it also was a new stage of the development of European art. It marked the end of the classical period that began in the Renaissance.

The Towing of a Boat in Honfleur

Claude Monet, 1864

Oil on canvas, 55.2 × 82.1 cm

Memorial Art Gallery of the

University of Rochester, New York

The Impressionist movement, thought, did not impose itself as an evidence. It initiated very serious discussions and criticism. It is true that the Impressionists marked an important distance with the classical school of art and this could only cause debate. The difficulty, for the Impressionists, to display their works illustrate the tension that accompanied the birth of this artistic movement.

Le Pavé de Chailly dans la Forêt de Fontainebleau

Claude Monet, 1865

Oil on canvas, 97 × 130 cm

Ordrupgaardsamlingen, Copenhagen

For instance, Albert Wolff, a critic, wrote after the second Impressionist exhibition: “Try to make Monsieur Pissarro understand that these trees are not violet, that the sky is not the colour of fresh butter (…) and that no sensible human being could countenance such aberrations (…) try to explain to Mr. Renoir that a woman’s torso is not a mass of decomposing flesh with those purplish-green stains”.

Scene of War in the Middle Ages or The Misfortunes of the Town of Orléans

Edgar Degas, 1865

Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 81 × 147 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The Impressionists and the classical school of Art

As said before, the group of young artists – the future Impressionists – was formed in the early 1860s. Claude Monet, the son of a store owner from Le Havre, Frédéric Bazille, the son of wealthy parents from Montpellier, Alfred Sisley, a young Englishman born in France, and Auguste Renoir, the son of a Parisian tailor, all came to study painting in the free studio of professor Charles Gleyre in 1862.

Mouth of the Seine River in Honfleur

Claude Monet, 1865

Oil on canvas, 89.5 × 150.5 cm

The Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena (California)

For them, Gleyre was the embodiment of the classical school of art. At the time he met the future Impressionists, Charles Gleyre was sixty years old. Born in Switzerland, on the shore of Lake Lean, he had lived in France since his childhood. Having graduated from the School of Fine Arts, Gleyre spent six years in Italy.

Avenue of Chestnut Trees near La Celle-Saint-Cloud