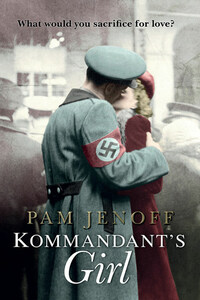

For several years after my return to the United States in 1998, I had wanted to write a novel that captured the experiences in Poland, and particularly with the Jewish community there, that had affected me so profoundly. I was captivated for some time by the vision of a young woman nervously guiding a child across Krakow’s market square during the Nazi occupation. But it was not until early 2002, when I had the good fortune to ride a train from Washington, DC to Philadelphia with an elderly couple who were both Holocaust survivors, that I learned for the first time the extraordinary story of the Krakow resistance. And with that historical foundation, Kommandant’s Girl was born.

There are so many people who have walked this path with me from concept to finished novel. I am eternally grateful to my family, friends and colleagues, including my mother and father, my brother Jay (yes, you can read it now), Phillip, Joanne, Stephanie, Barb and others too numerous to mention for their endless interest, patience and love. I would also like to thank my writing instructor, Janet Benton, and the other writers who have offered selfless guidance, fellowship and support every step of the way.

This book would not have been possible without the relentless efforts of my wonderful agent, Scott Hoffman of Folio Literary Management, who recognised the potential in this book before anyone else, worked tirelessly to refine it, and persevered long after most others would have quit. I would also like to salute my brilliant editor, Susan Pezzack, for her many insights in bringing this work to life and for making a dream come true.

Finally, I have come to realise through the writing of this book that the term “historical fiction” is somewhat of an oxymoron. While creating imaginary characters and events, I have endeavoured to remain true to the spirit of those who lived and died during World War II and the Holocaust, and to realistically depict the full range of human strengths, frailties and emotions brought out by this tragic and remarkable era. To this end, I would like to express my boundless admiration for the Jewish communities of Poland, and all of Central and Eastern Europe, past, present and future: your courageous struggle is an inspiration to us all.

As we cut across the wide span of the market square, past the pigeons gathered around fetid puddles, I eye the sky warily and tighten my grip on Lukasz’s hand, willing him to walk faster. But the child licks his ice-cream cone, oblivious to the darkening sky, a drop hanging from his blond curls. Thank God for his blond curls. A sharp March wind gusts across the square, and I fight the urge to let go of his hand and draw my threadbare coat closer around me.

We pass through the high center arch of the Sukennice, the massive yellow mercantile hall that bisects the square. It is still several blocks to Nowy Kleparz, the outdoor market on the far northern edge of Kraków’s city center, and already I can feel Lukasz’s gait slowing, his tiny, thin-soled shoes scuffing harder against the cobblestones with every step. I consider carrying him, but he is three years old and growing heavier by the day. Well fed, I might have managed it, but now I know that I would make it a few meters at most. If only he would go faster. “Szybko, kochana,” I plead with him under my breath. “Chocz!” His steps seem to lighten as we wind our way through the flower vendors peddling their wares in the shadow of the Mariacki Cathedral spires.

Moments later, we reach the far side of the square and I feel a familiar rumble under my feet. I pause. I have not been on a trolley in almost a year. I imagine lifting Lukasz onto the streetcar and sinking into a seat, watching the buildings and people walking below as we pass. We could be at the market in minutes. Then I stop, shake my head inwardly. The ink on our new papers is barely dry, and the wonder on Lukasz’s face at his first trolley ride would surely arouse suspicion. I cannot trade our safety for convenience. We press onward.

Though I try to remind myself to keep my head low and avoid eye contact with the shoppers who line the streets this midweek morning, I cannot help but drink it all in. It has been more than a year since I was last in the city center. I inhale deeply. The air, damp from the last bits of melting snow, is perfumed with the smell of roasting chestnuts from the corner kiosk. Then the trumpeter in the cathedral tower begins to play the hejnal, the brief melody he sends across the square every hour on the hour to commemorate the Tartar invasion of Kraków centuries earlier. I resist the urge to turn back toward the sound, which greets me like an old friend.

As we approach the end of Florianska Street, Lukasz suddenly freezes, tightening his grip on my hand. I look down. He has dropped the last bit of his precious ice-cream cone on the pavement but does not seem to notice. His face, already pale from months of hiding indoors, has turned gray. “What is it?” I whisper, crouching beside him, but he does not respond. I follow his gaze to where it is riveted. Ten meters ahead, by the arched entrance to the medieval Florian Gate, stand two Nazis carrying machine guns. Lukasz shudders. “There, there,