ANNE O’BRIEN taught history in the East Riding of Yorkshire before deciding to fulfil an ambition to write historical fiction. She now lives in an eighteenth-century timbered cottage with her husband in the Welsh Marches, a wild, beautiful place renowned for its black-and-white timbered houses, ruined castles and priories and magnificent churches. Steeped in history, famous people and bloody deeds, as well as ghosts and folklore, the Marches provide inspiration for her interest in medieval England.

Visit her at www.anneobrienbooks.com

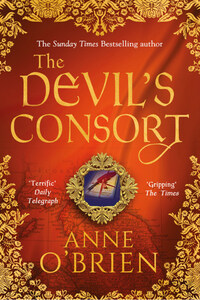

Also by

ANNE

O’BRIEN

VIRGIN WIDOW

DEVIL’S CONSORT PURITAN BRIDE THE KING’S CONCUBINE

Marriage Under Siege

Anne O’Brien

My Lord,

If you have received this you will be free and in Ludlow with Mary and Joshua. I know that you blame me for your imprisonment at Leintwardine. It was not by my hand, but I fear that nothing I can say, considering our past history, will put my actions into a better light.

I have done what I can to put matters right between us and pray that it will be enough. When we married, I did not realise that divided loyalties, even when they do not exist, could cause so much suspicion and pain.

I pray for your safety. As I told you at Leintwardine, I do not, for one moment, regret our marriage. But sometimes destiny is a stern master and cannot be gainsaid. I understand your sentiments towards me. I am only sorry that I was never able to prove my love for you. I have never found it easy to explain my emotions—and would not have burdened you with them anyway.

For the rest, I cannot write it.

God keep you safe.

Honoria

They drew rein at the crossroads.

‘So, Josh—what now? Ludlow is closer than Brampton Percy and it has the guarantee of a welcome and a few home comforts. Do you go home?’

‘Perhaps not.’ Sir Joshua Hopton, eldest son and heir to one of the foremost Parliamentarian families in Ludlow, tried without success to tuck his cloak more securely round him. Rain dripped from the brim of his hat, but was ignored. They were so wet that it mattered little. ‘I have a mind to witness your homecoming as the new Lord—so I will forgo the delights of Ludlow until tomorrow.’

‘Well, then, let us go on. You will no doubt be as welcome as I am.’ A swirl of low cloud and mist hid the faint gleam of cynicism in the cold eyes of Sir Joshua’s companion as he shortened his reins, slippery from the wet. ‘More so, I venture.’

Without further conversation, they turned their horses to the west, towards the Marches’ stronghold of Brampton Percy as a fresh flurry of rain, heavily spiked with hail, pattered with diamond-bright intensity on men and horseflesh alike.

Their escort fell in behind.

An hour later the two round towers, built to overawe the local populace and protect the gateway with its massive double portcullis, loomed dark and forbidding before the small party of travellers. The March day was now drawing to an early close with scudding clouds and a chilling wind that whipped the travel-stained cloaks, tugged at broad-brimmed hats and unsettled the weary horses. It was not weather in which to travel, given the choice. Nor was the castle a welcoming prospect, but the two men approached confidently, knowing that they were expected and that the gate would not be closed against them.

It had been a long journey from London to this small cluster of houses and its imposing castle of Brampton Percy in the depths of the Welsh Marches. Days of poor weather, poor accommodation and even poorer roads in the year of Our Lord 1643. The War, now into its second year, had given rise to any amount of lawlessness, encouraging robbers and thieves to watch the two men with their entourage and their loaded pack horses with more than a little interest, but they had finally arrived at their destination without event. Perhaps the air of determination, of watchfulness and well-honed competence that surrounded the travellers, together with the clear array of weapons, had kept the footpads at bay. Certainly none had been prepared to take the risk.

More problematic had been the small groups of armed forces that frequently travelled the roads in these troubled times. It was not always easy to identify their affinity, to determine friend from foe, Royalist from Parliamentarian. For these two travellers and their dependants, a Parliamentarian force would have signified a friend, an exchange of news, some protection if they chose to travel on together. A Royalist party would have signalled at best instant captivity and a hefty ransom after a long and uncomfortable imprisonment in some local stronghold, at worst, ignominious death, their bodies stripped of everything of value and left to rot in a roadside ditch. So they had travelled carefully and discreetly, their clothes dark and serviceable, nothing to advertise their economic circumstances or social standing other than the quality of their horseflesh and the tally of servants who accompanied them.

On this final afternoon in the rural fastness of north-west Herefordshire, the heavy showers of rain and sleet had cleared, but there was no glimmer of sun or lightening of the heavy clouds, making the sight of the gatehouse doubly welcome. The village street was silent except for chickens scratching in the mud, the inhabitants taking refuge from the elements and the uncertainty, but the travellers were aware of watchful eyes as they passed. Their hands tightened on their sword hilts. No one could afford to be complacent, even when the assurance of hospitality was close at hand.