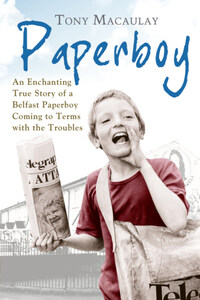

Tony Macaulay

Paperboy

An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter 1 - Recruitment and Induction

Chapter 2 - Hoods and Robbers

Chapter 3 - The Belfast Crack

Chapter 4 - Secrets at School

Chapter 5 - A Rival Arrives

Chapter 6 - Three Steps to Heaven

Chapter 7 - Tips and Investments

Chapter 8 - Good Livin’

Chapter 9 - Wider Horizons

Chapter 10 - Paper Mum

Chapter 11 - Scouts, Bombs and Bullets

Chapter 12 - A Final Verbal Warning

Chapter 13 - Sharing Streets with Soldiers

Chapter 14 - Save the Children

Chapter 15 - Peace in the Papers

Chapter 16 - Puppy Love

Chapter 17 - Musical Distractions

Chapter 18 - Across the Walls

Chapter 19 - Winners

Chapter 20 - The Last Round

Acknowledgements

Biography

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my parents, Betty and Eric Macaulay, their good friends, Ella and Harry Maguire, and all the voluntary youth leaders who kept young people off the streets and safe in Belfast in the 1970s.They are the unsung heroes of the Troubles.

Introduction

I was a paperboy. This never made it to my CV. So, just for the record, the dates of employment were 1975–1977. The place was Belfast.

I delivered the evening Belfast Telegraph – forty-eight Belly Tellys each night in the darkness. Belfast in the seventies was like the newspapers I delivered. Everything was black and white, albeit Orange and Green. Everything got smudged and ruined, like dark ink from the stories that dirtied my hands every day. But there were chinks of colour too, like in the weekly glossy magazines I provided to the more affluent customers of the Upper Shankill.

I was a paperboy. Aged twelve. Thin and easily crumpled. Blown around the streets by greater forces. More smart than tough. Yearning for peace, but living through Troubles.

And yet, as you will learn in these slightly less fragile pages, I was happy with my calling. I was a good paperboy. I delivered.

Chapter 1

Recruitment and Induction

I was too young, so I was. You had to be a teenager to be a paperboy for Oul’ Mac. He gave my big brother the paper round in our street when he was thirteen. By the time I was twelve I was jealous of the money and the status. I couldn’t wait an extra year to get my foot on this first rung of the employment ladder. So one wet Belfast night I persuaded my brother to introduce me to Oul’ Mac and to inform him of my eagerness to enter his employment.

My first job interview was a nerve-wracking experience.

‘Have you any rounds going, Mr Mac?’ I asked. (You never called him Oul’ to his face.)

‘Aye, alright,’ said Oul’ Mac, ‘but no thievin’, or you’re out!’

I concluded that my application for the post had been successful. He hadn’t even asked if I was thirteen yet, so I didn’t have to tell lies. Lies were a sin back then.

So, at the age of twelve, I set out on my career as a paperboy. My fear of age exposure gradually dissolved as I approached my thirteenth birthday, when I would become completely legit. I no longer had nightmares about being arrested by the RUC for underage paper delivery.

No sooner had I taken up my new position than my big brother decided that paper rounds were only for wee kids and he summarily left the arena of newspaper delivery entirely to me. I did nothing to dissuade him. I was delighted. Now the papers would be my exclusive territory. My wee brother was still more interested in Lego and Milky Bars and Watch with Mother, but I could sense that he envied my new career and was longing for the day when he too could follow in the family tradition.

Oul’ Mac liked me. He said I was a good, honest boy. This was important to him. It meant you wouldn’t steal the paper money that you collected from the customers on a Friday evening. He was a tough boss, though. He sacked wee lads all the time. Half our street had been sacked by Oul’ Mac. But if you did a good job, with no cheek to the pensioners and no thieving, he didn’t shout at you much and your position was secure. Oul’ Mac had been a newsagent on the Upper Shankill for decades: no one could remember anybody else ever delivering the papers up our way. But he was getting on a bit now. Oul’ Mac smoked and said ‘f**k’ a lot. Of course, most men smoked and said ‘f**k’ a lot, but Oul’ Mac did both, simultaneously and ceaselessly. He was a thin man with no beer belly to hold up his tatty trousers, so he was always hoisting them up in between cigarette drags. I never saw him smile, but sometimes his eyes twinkled and I couldn’t work out whether he was coughing or laughing. On these rare occasions when his mouth opened wide, I would worry for his last few wobbly, yellowing teeth, teetering on the brink.

Oul’ Mac had dark yellow fingers, where the nicotine of ten thousand cigarettes blended with the printing ink of a million newspapers. His skin was dark and leathery because he was outdoors most of the time, filling and emptying his van. His face and arms were also a yellowy hue. Mrs Mac said he was bad with his liver. He had only a few remaining tufts of hair, mostly white, but in places the same dark yellow as his stained hands. His hair always stood upright, gelled in place by the binding glue of a million magazines on his fingers.