4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © Philip Hensher 2018

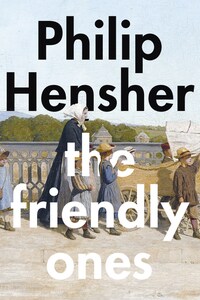

Cover image by Albert Anker (1831–1910)

Kleinkinderschule auf der Kirchenfeldbrücke, 1900, oil on canvas

Gottfried Keller-Stiftung, Bundesamt für Kultur, Bern

Depositum im Kunstmuseum Bern

Extract from ‘Second’ taken from Happiness by Jack Underwood (Faber & Faber). Copyright © Jack Underwood, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd.

The right of Philip Hensher to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008175641

Ebook edition: March 2018 ISBN: 9780008175665

Version: 2018-01-30

If I lived in a cave and you were my only visitor,

what would I tell you that the walls had told me?

That people are unfinished and are made between

each other …

JACK UNDERWOOD, ‘Second’

… amid the millions of this great city it is difficult to discover who these people are or what their object can be …

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, The Hound of the Baskervilles

1.

Towards the end of the afternoon, Aisha got up and stood at the garden window. The arrangements for the party had been in place since the morning – the hired barbecue, red and shiny under the elm tree, the festoons over the bushes, the torches lined up along the shrubbery. Over the fence, the old man was up a ladder against a fruit tree. He had been sweeping fallen white blossom from his lawn, and now had found something to do where he could see his neighbours better. Inside the room, the Italian was continuing to talk. Her mother and father were still listening.

‘Really?’ Nazia said inattentively. She could not see this one as a son-in-law. He was bald; his brown sweater hung, unravelling, around his dirty wrists. His party clothes were underneath. Aisha had been an eager, encouraging member of his audience until early yesterday evening, and then, quite abruptly, had wilted into silence and bored disinterest, passing him on to her parents, like a pet she had passionately wished for before finding the task of caring for it too much.

‘In Sicily, we often have such parties,’ the Italian was saying. ‘But it is too hot, in the summer, to have parties during the day where food is served. We wait until nine or ten o’clock in the evening, and then we eat cold food, perhaps some pasta. We would not grill meat like this, in the open air.’

‘Really?’ Sharif said, in his turn. A bird was singing in the elm tree, a loud, plangent, lovely note, as if asking a question of the garden. Underneath, the light fell through the leaves, dappling the lawn, the shiny red box of the barbecue, the white-shirted help, now talking quietly to each other, raising their eyes quizzically, serious as surgeons.

Nazia had felt she had done everything that she could have for Aisha’s Italian. They had taken him out to an Italian restaurant in Sheffield on Friday night, said to be very good, where he had poked suspiciously at his plate and explained about Sicilian food. They had gone out for the day into the countryside on Saturday, where Sharif had got lost and the stately home had failed to impress. She had cooked a real Bengali meal last night that Enrico couldn’t eat, and had said so. This morning, Aisha was supposed to take him for a walk in the neighbourhood, through the woods, but her change of heart yesterday had done for that. ‘Oh, Mummy,’ she had said, throwing her hands up, when Nazia had suggested it after breakfast. ‘Don’t be so dreadfully boring. I can’t think of anything worse. We’ll be perfectly happy just reading the paper.’

They had been in the square red-brick house almost four months. It was perfect, resembling a child’s first drawing of a house, with a square front, a door with brass knocker, windows to either side, and a chimney on both right and left. The purple front door had been changed to imperial blue, the kitchen modernized, the fitted carpets removed and the parquet flooring re-polished, the avocado bathroom altered to white: everything had been done under Nazia’s direction and control, but there had been no official opening.