![]()

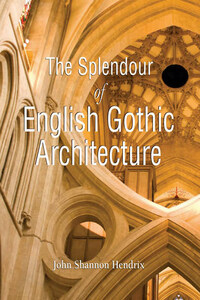

Nave vault, 1475–1490. Sherborne Abbey.

The purpose of this book is to examine and celebrate the richness of English Gothic architecture, in its use of materials, light, space, pattern, texture, and colour. Cathedrals and churches in England are among the most beautiful buildings in the world; they display less material splendour, but a more spiritual or experiential splendour. The experience of many of the buildings is unparalleled: being in the buildings, it is possible to find a sense of fulfillment through pleasure in the senses, intellectual stimulation in the complex structures and patterns, and the spirituality to which the spaces are devoted. The buildings make possible an architectural experience which is unique, and have a richness beyond most buildings, especially modern buildings. Architecture is closer to reaching its potential in these buildings than in most others: its potential to create a fulfilling experience in which human identity is understood in relation to nature and the divine. The architecture speaks, through its materials, spaces, structures, textures, and patterns, to both the senses and intellect; it is among the most poetic of all architecture, and is among the closest of all buildings which form art while still fulfilling the aspirations of architecture. The hope of this book is for the details of the buildings to be seen together as a whole, as a myriad of variations on a theme, which, taken together, represent an extraordinary architectural experience.

The development of English Gothic architecture throughout the Middle Ages, from 1180 to 1540, is relatively homogeneous and consistent, contributing to the same campaign, the same particular use of vocabulary elements, with surprising and innovative variations, and the same expressive intentions. Consistently throughout the development of English Gothic architecture, there is an intention in the architecture to express a poetic idea through the juxtaposition of non-structural geometries with the structural geometries of the architecture. Its characteristic “handwriting”, the linear networks, surface patterns, geometrical articulations, and spatial interpenetrations contribute to the creation of an architecture in which form contradicts function, resulting in a poetic expression. In order for architecture to be art, its form must contradict its function, as architecture, unlike other arts, can never be free and independent from its function. The cathedrals and churches of English Gothic architecture contribute to an expression of a coherent idea, representing the theology, philosophy, and epistemology (Scholasticism) of medieval England. The buildings are intended as catechisms, as three-dimensional models for didactic purposes, to represent and communicate basic ideas about man, God, and being to everyone. Such concepts of the structure of the universe, being, and intellect permeated the culture of medieval England, and from 1180 to 1540 contributed to a homogeneous cultural expression, particularly in the architecture of the cathedral. Cathedral architecture developed as a response to the zeitgeist of the era; there was little concept of individual artistic expression or creativity. The result is a lasting representation, in built form, of the theology, philosophy, and epistemology of a civilisation in the Middle Ages in England.

The architecture is presented chronologically, beginning at the end of the 12th century and culminating at the beginning of the 16th century. The chronological development is divided into periods, periods which were established by Thomas Rickman in the Attempt to Discriminate the Style of Architecture in England in 1815. The periods are Early English (1180–1250), Early Decorated (1250–1290), Decorated or Curvilinear (1290–1380), and Perpendicular (1380–1540). The names given to the periods by Rickman are not exhaustive or completely accurate in relation to the architecture of the periods, but they suffice to provide the simplest and most accepted way of naming the periods.

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Ground (detail), 1823. Oil on canvas, 87.6 × 111.8 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Master of Girart de Roussillon, Building Site, second half of the 15th century. Page from the illuminated manuscript Girart de Roussillon: chanson de geste. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

Nave, 1093-mid-12th century. Durham Cathedral.

The chapter “Early English” presents architectural developments at Canterbury, Wells, Lincoln, Winchester, Ely, Beverley, Chester, York, Salisbury, Worcester, Southwell, and Gloucester. Canterbury Cathedral is the first English Gothic cathedral, where the work of William of Sens and William the Englishman marks a departure from Norman or Romanesque precedents, where forms and approaches are invented which would be influential throughout the development of English Gothic architecture. The first phase of building at Wells, including the nave, was contemporary with the first phase of building at Lincoln, and the two buildings represent different departures from the architecture at Canterbury, but each equally and distinctively defining English Gothic architecture, Wells more in its homogeneity and Lincoln more in its syncretism. The east and west transepts at Lincoln show the influence of Canterbury in an experimental approach to spatial relationships and a variety of materials. The rose windows in the west transept, along with the Dean’s Eye and Bishop’s Eye, are the first great examples of stained glass in an English Gothic cathedral. Ely Cathedral was the first to exhibit the influence of Lincoln, visible in the detailing of the west front and the Galilee Porch, in particular the overlapping double arcading. The eastern part of Winchester Cathedral, the Lady Chapel, shows the influence of Lincoln in the early 13th century. The overlapping double arcade occurs at Beverley Minster, along with Purbeck shafts and openwork arcading, in a purification of the intentions at Lincoln. The elevations of the south transept of York Minster, begun around 1220, are similar to Lincoln and Beverley, as are the elevations of the retrochoir of Worcester Cathedral, built in the 1220s; the vault of Worcester retrochoir is a tierceron vault derived from Lincoln. The motifs of the retrochoir elevations are continued into the choir at Worcester.