Foreword

I have always enjoyed country houses. There is something about their completeness, with their different rooms and offices catering to almost every need, making up a microcosm of a complete world, that is very satisfactory to me. But, as a child, wandering around the homes of my parents’ friends and relations, I was aware that I was looking at the remains of a way of life that, with rare exceptions, was no longer being lived in by them. Those empty attic rooms, often still boasting an iron bedstead or a dusty cupboard with vacant nameplate holders on the doors, spoke of a once-crowded place, peopled then only by ghosts. Those echoing stables, full of abandoned toys and rusting gardening equipment, those vast kitchens, jammed with discarded luggage and broken bicycles and signs for use in the village fête, were haunted to my childish eyes by shadows of what used to be.

Of course, I grew up in the sad years for these monuments to the past. They had lost their value as the aristocracy largely threw in the towel after the war, and in the 1950s they could hardly be given as presents. Instead, palace after great palace, those that were not considered suitable for some new and frequently inappropriate role, fell victim to the demolition ball, and an immense part of our nation’s heritage was literally thrown away. Until 1974, when the new director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Roy Strong, decided to stage an exhibition, The Destruction of the English Country House, and it is not an exaggeration to say that everything changed, almost overnight. We woke up to the idea that these houses were an integral part of our history, that the life formerly lived in them had involved us all, whether our forebears had been behind the green baize door or in front of it, that they were not simply huge and unmanageable barns, no longer viable without sufficient staff, but expressions of our national character that we should be proud of.

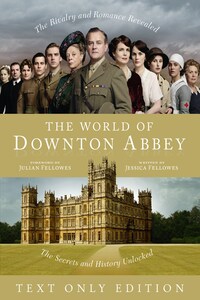

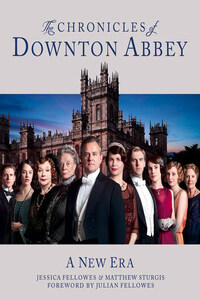

And as we learned to love them again, so a younger generation invented a new way to live in them. They didn’t mourn the servants they had usually never known. They simply saw the space and its possibilities. The big kitchens were re-opened and the horrible converted ante-rooms and passages that had served as kitchens for our parents’ generation were abandoned. But this time, the family chose to occupy the kitchens in their own way, importing televisions and sofas and toys and making them right for the way we live now. Helpers did not sleep upstairs in the garrets but came in from the village and called the owners by their Christian names and felt, quite rightly, that they had a stake in making the house work. In a way, the landowners reinvented themselves, as the aristocracy has done so many times before, and found a place, for themselves and their houses, in modern Britain. This was perhaps the main inspiration for the series, Downton Abbey, because we did all feel that were we to go into this territory, it must be right for our present zeitgeist to give equal weight, in terms of narrative or moral probity or even likeability to both parts of the community of a great house, the family and their servants. This I hope we have done, favouring neither group over the other, which I am convinced remains one of the principal strengths of the show.

Like most of the good things in my life, Downton Abbey came about entirely by chance. I had been trying to get a completely different project off the ground with the producer, Gareth Neame, and when at last we realised it was not going to fly, we met for dinner to call it a day. It was then that Gareth suggested venturing back into the territory of a film I had written some years before, Gosford Park, but this time for television, and that is how it began. Gosford was set in a large country house in November 1932 and it dealt with a shooting party and their servants, both those working in the house and for the guests, so it was clear at once what Gareth wanted. I was a little nervous initially, at the risks of asking for a second helping, but the idea grew on me and so Downton Abbey was born. Television – or rather, a television series, with its open-endedness, with its unlimited time to develop any character – held possibilities that the space allowed for a film narrative could not offer. We decided at once to retreat twenty years to 1912, since the underlying theme of Gosford Park had been that it was all coming to an end; but we didn’t want to go further back than that as we both agreed that we needed the action to take place in a recognisable universe – with cars and trains and telephones and many other modern devices, albeit in embryo, which defined the period clearly as the parent of the present day.