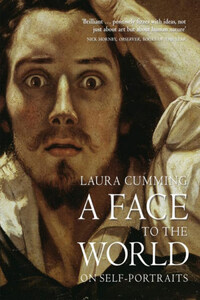

‘We were created to look at one another, weren’t we?’

Edgar Degas

Charles Dickens once said that he lived in perpetual dread of any sudden new discovery about Shakespeare: the revelation of a letter, an image, a biographical fact, anything that might disturb his life’s fine mystery. The little that was known was dismaying enough – that the Universal Genius had a hard head for business and thought nothing of pursuing the tiniest of debts through the courts; that the author of the Tragedies also found time to pester the government about the state of the roads around Stratford. At least nobody really knew what Shakespeare looked like. To Dickens’s relief, there was no face to disillusion the faithful since not one of the portraits for which claims of authenticity were so often published in Victorian times was made by an artist known to have met him. The ruffed bust of the bard at Stratford, the Chandos dandy with his golden earring: these could be regarded as false idols for a credulous population. Dickens despised the public’s need for a face and could not contain his scorn when asked to help fund a statue of Shakespeare, replying that he would not contribute a farthing for a likeness because the work must be the only lasting monument.>1

The ideal Shakespeare for Dickens is the Shakespeare we have, a genius and an absolute blank. Immortal, invisible, unimaginably wise: something like God Almighty. This is exactly the comparison that occurs to Jorge Luis Borges in Everything and Nothing, his parable of Shakespeare’s extraordinary elusiveness as an actual person. Borges imagines a conversation at the pearly gates between the two great creators in which Shakespeare, having been so many other people in his art, appeals to God to let him be just one man at last. But God offers not the slightest hope: ‘I too have no self; I dreamed the world as you dreamed your work, my Shakespeare, and among the shapes of my dream are you, who, like me, are many men and no one.’>2 Shakespeare has no unified self, no single identity and certainly no fixed appearance. In fact, he is too great to have been visible at all; Borges describes him as a hallucination, a dream dreamt by nobody, a cloud of ethereal vapour.

For all those who would prefer Shakespeare to remain invisible many more long for a definitive face, perhaps hoping to find a trace of character in its expression, or to feel a direct line of communication opening before them, or just for the simple and irreducible fascination of knowing what Shakespeare looked like. This curiosity is not to be despised. You do not have to believe, like Schopenhauer, that the outer man is a picture of the inner, or that the face is a manifestation of the soul. From the infant’s ability to read two dots and a dash as primitive features barely before its eyes can focus, to the instinctive imagining of the unseen correspondent or the speaker on the other end of the line, from our mass observation of passers-by in the street to the rage for Facebook, a compulsion to look at our fellow beings unites us. How can one not take an interest in faces, real or represented? It is almost a test of human solidarity. Degas told Sickert he always took the omnibus across Paris because he could never see enough people from inside a closed carriage. ‘We were created to look at one another, weren’t we?’>3

Yet the strain of antipathy towards portraiture that runs in and out of history, that once demoted it well below battle scenes or bathing nymphs, that derides it as face-painting and mistrusts its version of the truth, has something to do with faces and not just pictures. For faces do not always fit, people do not look as they should. Appearances may create a spurious sense of intimacy when they look right for the part – this is just how one imagined the famous person – or sudden and dismaying estrangement when they don’t. Delacroix, passionate in painting, has a prim little toothbrush moustache. Stravinsky is a lugubrious bureaucrat. Rothko, his aim so spiritual, is a heavy lug in blue-tinted glasses. Almost everyone would prefer a better Shakespeare than the egghead of the First Folio engraving (which Ben Jonson, having known the original, worryingly endorsed on the opposite page) and nobody can stomach the portly dolt with his cushion and quill commemorated in the bust at Stratford. If Shakespeare made us most fully human to ourselves then surely he should look more like some other great soul; Shakespeare should look more like Rembrandt.