4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

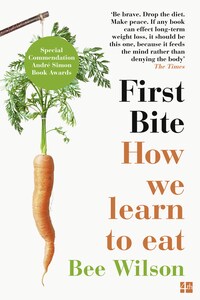

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by 4th Estate

This 4th Estate paperback edition 2016

Copyright © Bee Wilson 2015

Cover image © Mat Taylor

The right of Bee Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

‘An Evening in Terezin’ from I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children’s Drawings and Poems from Terezin Concentration Camp 1942–1944 by Hana Volavkova, copyright © 1978, 1993 by Artia, Prague. Compilation © 1993 by Schocken Books. Used by permission of Schocken Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007549726

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780007549719

Version: 2016-11-10

Some find the whole matter of eating easy, while others find it hard. I used to be on the wrong side of this great divide and somehow, to my own surprise and relief, leaped over to the other side. This book is my attempt to explore how this switch was possible.

You don’t have to look far in our world to encounter people – of all sizes – who relate to food in chaotic ways. The chaos can take many forms: compulsive overeating, undereating, or extreme pickiness. Some people become so obsessed with the purity of what enters their mouths that they cannot accept invitations to eat with friends. It is a lonely occupation, being someone who wrestles to control their responses to food, given that modern life is steeped with things to eat, both real and imaginary. Snacks assail us at the checkout; dream feasts tease us from hoardings, newspapers and TV cooking shows.

Without ever quite having a full-blown eating disorder – though I came close – I managed to make myself pretty miserable about eating for the best part of a decade, from the middle school years to young adulthood. I probably appeared fine: a bit overweight, nothing more. But food was my main relationship, and – although it had some of the thrills of romance, especially when I was in the kitchen with a hunk of sweet brioche dough – it wasn’t a stable or sustaining kind of love. We talk in a sickly way of ‘indulgent’ foods, but when you are trapped in compulsive habits of dependency on them, it does not feel like being pampered. There were days when I gave myself up to consuming guilty treats. Other days were for not eating, which was even worse, taunting myself with the foods that I wouldn’t permit myself.

Thankfully, that phase of life now seems distant. Eating well – by which I don’t mean ‘clean eating’ or raw juice fasts but regular meals of real, flavoursome food – just isn’t that complicated for me any more. Now that I am through on the other side, I can see that over a period of months, if not years, I learned to master a series of skills that I’d once deemed insurmountable. I learned that it was OK to eat a hearty meal when I was hungry; but also OK to stop when I was full. My cravings for pastries lessened and my cravings for vegetables increased. There are still plenty of things I worry and obsess about, believe me, but my own eating is seldom one of them. Dinner is just dinner: nothing more nor less than the high point of the day.

In our house, as in many others, the battleground over food has shifted to the children. As a parent trying to get my three children to eat healthily – but not obsessively so – I have sometimes felt as lost as I once did about my own eating. After the milk stage (and that was hard enough) none of the skills of feeding came naturally. How do you promote vegetables to an ironic teenager in a way that isn’t counterproductive? What do you do when your daughter comes home and says her friends have started skipping lunch? How do you keep a sense of proportion about fat and sugar without giving in completely to the ultra-processed food that is now ubiquitous?