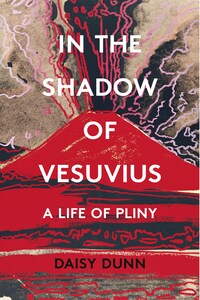

Pliny

A new biography of Pliny the YoungerAD 79. Above the Bay of Naples, Mount Vesuvius is spewing thick ash into the sky. The inhabitants of nearby villages stand in their doorways, eyes cast on the unknown. Pliny the Elder, a historian, admiral of the fleet, and author of an extraordinary encyclopaedia of Natural History, dares to draw closer to the phenomenon. He perishes beneath the volcano. His seventeen-year-old nephew, Pliny the Younger, survives.The elder Pliny left behind an enormous compendium of knowledge, his Natural History offering observations on everything, from the moon, to elephants, to the efficacy of ground millipedes in healing ulcers. Adopted as his late uncle’s son, Pliny the Younger inherited his notebooks – his pearls of wisdom – and endeavoured to keep his memory alive. But what became of the young man after the disaster? Pliny resurrects the ‘father and son’ to explore their beliefs about life, death and the natural world in the first century AD. At its heart is a literary biography of the younger Pliny, who grew up to become a lawyer, senator, poet, collector of villas, curator of drains, and personal representative of the emperor overseas. Counting the historian Tacitus, biographer Suetonius, and poet Martial among his close friends, Pliny the Younger chronicled his experiences from the catastrophic eruption through the dark days of terror under Emperor Domitian to the gentler times of Emperor Trajan. Interweaving the younger Pliny’s Letters with ideas and extracts from Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, Daisy Dunn brings their world back to life. Working from the original sources, she celebrates two of the greatest minds from antiquity and their influence on the world that came after them.